Cawlyahan killing boo ons for sport and taking their camels because they could lol

The Sack of Serenli

Excerpt:

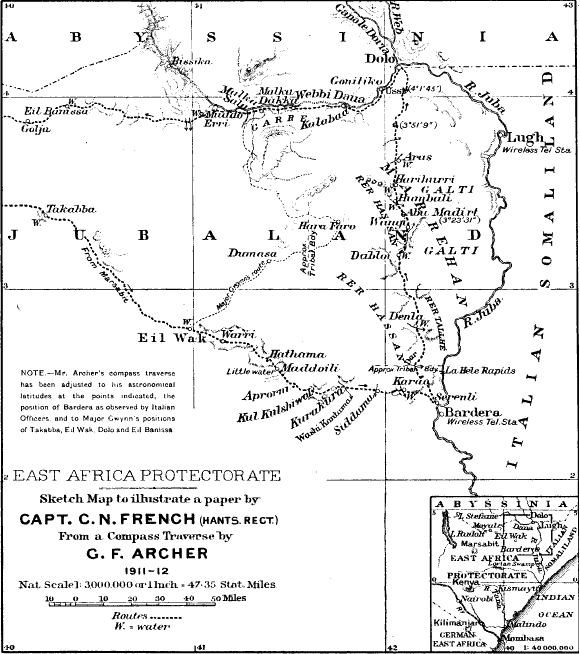

"On 2 February 1916, the disaster that British officials had feared would one day happen in the NFD occurred in neighboring Jubaland. There, a large party of northern Aulihan led by Hajji 'Abdurrahman Mursaal surprised and killed the Serenli DC, Lieutenant Francis Elliot, and many of the British garrison. It is important to understand the motives that lay behind the sack of Serenli. The incident actually arose from a dispute between Aulihan and Marehan Somalis not long after the outbreak of the First World War and from which a series of raids and reprisals had followed. Following the deaths of nine Marehan at the hands of northern Aulihan and the looting of hundreds of camels, Lieutenant Elliot had publicly given 'Abdurrahman Mursaal an ultimatum to surrender the stolen animals to him within three days. Instead, the government-paid Reer Waffatu headman defiantly delivered a gift of black animals that, by Somali custom, constituted an open challenge to the Serenli DC. The undaunted, but injudicious, Elliot apparently was contemptuous of the threat and failed to take precautions. Instead, he continued his incredible practice of locking the garrison's rifles in the guardroom each evening before sunset. Moreover, he allowed a large contingent of Aulihan to camp just 100 yards from the boma.

At 7 p.m., while the askaris, or African soldiers, were settling down to evening meals, the Aulihan burst upon the British post. The Somalis set the surprised soldiers' huts on fire, and killed many of them as they fled the flames. By one account, 'Abdurrahman Mursaal himself is said to have shot Elliot beneath the ear with a revolver, and by another, to have donned Elliot's sun helmet after the raid. Dozens of Elliot's men were killed in the attack, while the survivors escaped across the Juba River to the nearby Italian post at Baardheere. The Somalis captured the company's maxim gun along with large quantities of arms and ammunition. 24 For the next 18 months, 'Abdurrahman Mursaal's northern Aulihan, strengthened by the acquisition of British weapons, held free reign over much of Jubaland and threatened British rule in the NFD as well. Indeed, a British officer with service in the region would later describe the Ogaden, of whom the Aulihan were a part, as "one of the most formidable fighting tribes in Africa" because of their mobility with their ponies, remarkable endurance, and the skill with which they wielded their spears.

The calamity that befell Elliot was undoubtedly partly his own doing. Nevertheless, the root of the problem stemmed from the unwillingness of higher authorities to bear the costs and accept the responsibilities of frontier administration. As had been the case with other frontier representatives from the inception of British rule in northern Kenya, officials in Nairobi had placed Elliot in a position of weakness and forced him to improvise in a hostile milieu. Like those other British administrators and contrary to official policy, Elliot found himself thoroughly entangled in local politics. Reading the official records from the period, the historian is struck by the degree to which colonial officers became involved in petty disputes. At times, this involved an attempt to prevent Somali groups, including the Aulihan whom the officer-in-charge of the NFD blamed for "crowding in," from wresting the Wajir wells from the Boorana and their Ajuran allies. In other cases, it entailed intrusion into feuds among the Somalis so that kaffirs, or infidels, became judges in conflicts that had heretofore been resolved by traditional means or with reference to shari'a, or Islamic law. Believing themselves impartial and just, British administrators presided over Somali shirs, mediated dia disputes, settled bride-wealth cases, and decided rights to watering sites. Such intervention could become dangerous for frontier representatives since they lacked legitimacy in Somali eyes and were without the means to enforce their decisions. That this was part of the reason for the Aulihan uprising is evidenced by the fact that, after the sack of Serenli, 'Abdurrahman Mursaal wrote a letter to King George V complaining of Lieutenant Elliot's partiality to the Marehan. Meanwhile, although the taxation of Somalis had not yet been sanctioned, the authorities had long since pressured them to surrender camels for government transport. Elliot, who took pride in his knowledge of the Somali language, did not fully appreciate the subtleties of Somali politics. Moreover, he counted too much on his own abilities, and consequently paid the ultimate price for his folly.

Understanding something of the character of 'Abdurrahman Mursaal is also important, not only for appreciating the events which lay behind the Aulihan rebellion, but also for comprehending the critical fact of why other Somali groups failed to join his resistance to colonial rule. 'Abdurrahman Mursaal was the son of Mursaal bin Omar, an important Ogaden leader in Italian Somaliland. The Aulihan chief and "holy man" came to the EAP after working for the Italian Benadir Company and running amiss of the Italian colonial administration. 'Abdurrahman Mursaal briefly served the Kismaayo administration after 1896, when the British sent him and 18 constables to establish a customs post at Serenli. 32 He became a leader of an Ogaden rebellion in British territory in 1898, however, and was involved in the death of the Jubaland subcommissioner, A. C. W. Jenner in late 1900. Nevertheless, the Reer Waffatu chief was soon working with the British again. So slight was the influence of the colonial authorities over the Somalis that they took help where they could get it. Some were not so ready to secure his services. John Hope, one of the first British officials to serve in the NFD, condemned 'Abdurrahman Mursaal's proclivities for independent action, and C. S. Reddie, a Jubaland Provincial Commissioner (PC), accused the Aulihan leader of gun-running. Nevertheless, Captain R. E. Salkeld, a British officer in Jubaland who subsequently became the PC, was willing to rely on 'Abdurrahman Mursaal. In fact, the Aulihan leader had the opportunity to meet with the EAP governor in 1915, and used his interview to promote his personal authority when he returned to Serenli. Obviously, the Aulihan leader was a man who took his own counsel, and one who could not be pushed too far. Elliot's inability to grasp this led to tragic consequences for him and his men as well as the Aulihan chief's followers when colonial troops finally suppressed their rebellion."

I still can't believe I fell for this trap from a northern freaking Reer Isaaq waryaa at least work on not talking like an indian with your DHs atleast Garad is Reer Cabdulle he can faan

I still can't believe I fell for this trap from a northern freaking Reer Isaaq waryaa at least work on not talking like an indian with your DHs atleast Garad is Reer Cabdulle he can faan

).

).