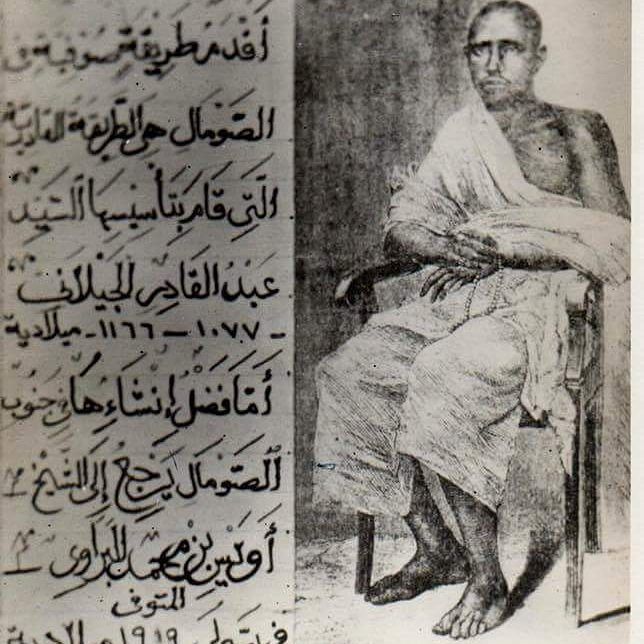

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abdallah_al-Qutbi - theologian, polemicist and philosopher. "Sheikh Al-Qutbi is best known for his Al-Majmu'at al-mubaraka ("The Blessed Collection"), a five-part compilation of polemics that was published in Cairo ca. 1919-1920 (1338). In this work, he launches a literary attack on the Wahhabis, the Salihiya, and Ibn Taymiyyah, all of whom he regarded as heretics Sheikh Abdullahi Qutbi, a disciple of Sheikh Abdulrahman Al Shashi and member of Qadiriyyah congregation, an Islamic school of thought or tariqah."

Shaykh Abdullahi al-Qutbi and the pious believer's dilemma: local moral guidance in an age of global Islamic reform Scott S. Reese

"Using the writings of the religious scholar `Abdullahi al-Qutbi, this article examines the ‘transregional’ nature of Muslim reformist discourse in the early twentieth century and the way in which the trajectories of individuals, objects and ideas cut across the largely imaginary boundaries traditionally used to divide the Middle East and Africa. African Muslims have maintained intimate ties with their non-African brethren across space through various intellectual, economic and political relationships throughout the history of Islam. However, they have also remained entwined across time via engagement with the more or less commonly accepted canon of the faith and what Talal Asad has termed the ‘discursive tradition.’ This essay demonstrates the persistence of these processes through the age of European colonialism into the early twentieth century. But equally important is the way in which the increasingly elaborate and rapid networks of empire created in the nineteenth century facilitated and intensified the interaction of both people and ideas helping create the modern horizontally integrated community of believers.

Sometime near the end of the First World War, Shaykh Yusuf Isma’il Nabhani, a retired Ottoman Qadi in Beirut, included the above statement as part of a publisher’s endorsement of a recently published set of pamphlets, the Majmu’a al Mubaraka or Blessed Collection. As a vociferous opponent of what we might term scripturalist reformers, such as Rashid Rida, Shaykh Yusuf’s testimonial promoting a text written by an advanced student at the prestigious al-Azhar University in Cairo openly hostile to that particular school of thought is unsurprising. What is more interesting, however, is that the collection was the work of a leading Somali Sufi, Shaykh Abdullahi al-Qutbi, whose sojourn in Egypt was relatively brief and whose reputation has always been presumed to not extend far beyond the Horn of Africa.

Nabhani’s endorsement of al-Qutbi’s Majmu’a is significant as a demonstration of what we might term the ‘transregional,’ and the way in which the trajectories of individuals, objects and ideas cut across the largely imaginary boundaries the academy has traditionally used to divide the Middle East, Africa and South Asia. Connectivity between Muslims across these regions, of course, pre-dates European colonialism. African Muslims have maintained intimate ties with their non-African brethren across space through various intellectual, economic and political relationships. However, they have also remained entwined across time via engagement with the more or less commonly accepted canon of the faith and what Talal Asad has termed the ‘discursive tradition.’

In part this essay demonstrates the persistence of these processes through the age of European colonialism into the early twentieth century. But equally important is the way in which the increasingly elaborate and rapid networks of empire created in the nineteenth century facilitated and intensified the interaction of both people and ideas, helping to create the modern horizontally integrated community of believers. I would like to do so by taking up what might best be described as the issue of moral guidance. The notion of moral economy is one that is frequently neglected by historians who often operate under the mistaken impression that the so-called ‘moralizing’ of pious `ulama has little bearing on the everyday lives of the average believer. I would, in fact, argue that the opposite is true. As an increasing amount of scholarship demonstrates, in Islamic contexts, religious discourse often functions as social discourse, where individuals look to the sacred for solutions to what they know all too well are the problems of the profane world. The importance of religious discourse as social discourse has been one central to the faith since its inception. However, from the second half of the nineteenth century various advances in transportation and print technology – what Jim Gelvin and Nile Green refer to as the ‘age of steam and print’ – had a transformative impact on the spiritual as well as everyday lives of believers.

Advances in steamship technology from the 1850s, along with the opening of the Suez Canal after 1869, rapidly increased the mobility of Muslims across the various European oceanic empires. The number of Muslims traveling on the Hajj during the second half of the century, for instance, increased exponentially with more believers taking part in the pilgrimage to Mecca than at any other time in the history of the faith. More importantly for purposes of this essay, the development of regularized steamship routes also led to the emergence of new networks of commerce, labor and religious scholarship. By the early twentieth century, regular steamer connections developed a transportation web that helped expand the circulation of East African labourers and merchants between the ports of the western Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean. Regional ports such as Berbera and Mogadishu in Somalia, and Mombasa and Zanzibar in British East Africa, were linked to a wider world via larger imperial hubs such as Aden in southern Arabia, Durban in South Africa and Suez in Egypt. Many of these routes were not new. Movement along them, however, was now faster, more regular and less expensive than ever before, allowing increasing numbers of Muslim (mostly) men to transcend what we might view as their traditional geographic networks.

In the spring of 1914, for instance, the Zanzibari `alim Muhammad al-Barwani left his island home on a German steamer that carried him to Suez via Tanga, Mombasa and Aden on a tour of Egypt and the holy places of the Levant. Al-Barwani recounted his journey in a rihlah or travel narrative titled Rihlat Abu Harith, in which he relates the wonders of streetcars and European style restaurants in Cairo and the solemnity of holy Jerusalem. However, he also mentions how, as he returned to his Beirut hotel one day, he unexpectedly ran into his cousin – who was traveling on business – in the lobby; a sure indication that travel to the Mediterranean was becoming more common for East Africans. In 1920, British consular officials in Egypt observed, with some alarm, the increasing numbers of Somali sailors and stockmen hanging about the canal ports of Suez and Port Said in what they regarded as a chronic state of underemployment. By the same token, the Somali `ulama – who traditionally looked to the holy places of the Hijaz (Mecca and Medina) and the learned centers of the Hadramaut (such as Tarim) for spiritual instruction – were beginning to discover first-hand the erudition of al-Azhar in Cairo. In addition to al-Qutbi, Somali students were reportedly attending the university in significant numbers as early as 1905. And, as we know from the endorsements of al-Qutbi’s essays appended to the end of the collection, there was at least one Somali religious scholar, Shaykh Umar b. Ahmad alSomali, who belonged to its faculty.

Of equal importance to Muslims in the age steam were advances in print technology – particularly the invention of the lithographic steam press – that revolutionized the accessibility of knowledge among Muslims. A great deal of research over the last decade and a half has focused on the proliferation of Islamic texts that accompanied the development of cheap lithographic printing. Most of this has centered on the impact of print in either the Arabic-speaking lands of the Middle East or Persianate South Asia. It is important to point out that African Muslims were no less avid consumers (and ultimately producers) of print. By the early twentieth century, religious texts printed in Cairo and Bombay were readily available in the coastal towns of East Africa, as were reformist newspapers such as Rashid Rida’s al-Manar.

By the second decade of the twentieth century, Muslim scholars in the region were also producing a small but steady stream of religious texts and periodicals of their own. These works ranged from popular newspapers like Shaykh al-Amin al-Mazrui’s al-Islah (Reform) to dense theological works such as Abdullahi al-Qutbi’s al-Majmu’a al-Mubaraka. They were concerned with matters ranging from language politics and local practice to broader reformist issues such as the application of shari’a and kafa’a (the Islamic legal notion that a woman may only marry one who is of the same – or superior – social, genealogical or moral rank). From one perspective, such works represent engagement with the intellectual and especially reformist trends of the period on the part of those we might describe as regional scholars. As such, these materials demonstrate a dynamic, multidirectional flow of knowledge, and the emergence of a more horizontally integrated and intellectually engaged global community of Muslims. Thus, not only are the ideas of what we have come to regard as the ‘big guns’ of reformist thought – such as Muhammad Abduh and Rashid Rida – disseminated to a large audience; but we begin to see local scholars actively engaging with those ideas, seeking to become part of a broad globalizing discourse. But we also see something else, the desire of these same intellectuals to help their constituents navigate this increasingly fraught arena of reformist discourse emerging in the early twentieth century.

The remainder of this essay focuses on the notion of ‘moral guidance’ through the writings of the Somali ‘alim, Shaykh Abdullahi b. Mu’allim Yusuf al-Qutbi, whose colourful career is representative of the increasingly fluid relationship between local and extra-local religious discourses in the early twentieth century. As we shall see, Shaykh Abdullahi’s magnum opus, a set of four pamphlets known as the Majmu’a al-Mubaraka or The Blessed Collection, was a theological work that addressed audiences on a number of registers. Until recently, the Majmu’a was regarded by the few scholars who have studied it – including myself originally – as a work of only local importance. Many viewed it as a highly polemical (even semi-hysterical) diatribe aimed at Sayyid Abdullah Hasan, the militant Somali reformist figure of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries sometimes referred to as the ‘Mad Mullah.’

Others regard it as a religious primer intended to instruct the heretofore only lightly Islamized nomadic populations of the northern Somali interior in the ways of ‘proper’ belief and practice. Both of these characterizations are at least partly correct, but it is important to remember that al-Qutbi was an al-Azhar-educated religious scholar with access to the vibrant intellectual atmosphere and what we might term the ‘boutique’ publishing scene of inter-war Cairo. As such, he was an individual with the learning and opportunity to actively engage with the more abstract currents of religious reform permeating the intellectual world of educated Muslims. More importantly, he was well placed to act as a mediating voice who could make sense of the oft times confusing and seemingly contradictory messages of religious reform for his less educated and far more provincial Somali kinsmen.

This brokering or mediating role is at its most clear in Shaykh al-Qutbi’s discussion of two related topics: taqlid (imitation) and takfir (apostasy or ‘the commission of unbelief’). Two seemingly esoteric, legalistic terms, taqlid and takfir were popular buzzwords that struck at the moral core of Islamic reform in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. What constituted correct – as opposed to incorrect – belief ? More importantly, how should one arrive at this determination? Could a believer make important moral and metaphysical judgments on his/her own – through the employment of ‘ijtihad’ – independent reason – or must one follow the example of some mediating authority via taqlid (or the emulation of a learned authority)? If they chose the latter option, was their faith defective? These were questions being asked not just by erudite intellectuals in the abstract but by far less lettered believers in the course of their everyday lives. Shaykh al Qutbi was representative of an African Muslim intellectual elite who actively sought to straddle both of these spheres. Through his writings, al-Qutbi sought to play an active role in the larger reformist debates of the period. But, as we shall see, he also sought via these same works to provide guidance to his followers through the labyrinth of modern reformist rhetoric.

Shaykh ’Abdullahi al-Qutbi and the Majmu’a al-mubaraka

Shaykh ‘Abdullahi ibn Mu’allim Yusuf al-Qutbi (1881–1951) is certainly one of the most colourful figures to emerge from the Sufi circles of East Africa in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Hailing from a prominent lineage of religious practitioners in the northern Somali region of Qolonqool, al-Qutbi’s family was among the earliest proponents of the Sufi revival of the later 1800s as enthusiastic followers of the Qadiri shaykh, Abd al-Rahman Zayla’i. An elder brother, Abu Bakr, even became head of the order upon Zayla’i’s death in the early 1880s. Like most prominent Somali `ulama, Shaykh Abdullahi studied the religious sciences first at the feet of his kin in Qoloonqol and then later under the tutelage of the most famous Sufi luminaries of his day. These included Shaykh Abd al-Rahman b. Abdullah ‘Sufi’ (d. 1905) of Mogadishu and Uways al-Barawi (d. 1909), the most celebrated Somali Qadiri shaykh of the period. Unlike most of his contemporaries, Shaykh Abdullahi was one of the few prominent Somali ‘alims of his day to complete advanced study not in Mecca or the Hadramaut, but in Cairo at the famous al-Azhar where he was in residence for a period of four years from approximately 1915–1919. There he studied the various religious sciences and wrote or revised the series of pamphlets that were to become the Majmu’a al-mubaraka.

Al-Qutbi’s Majmu’a has been particularly remembered as a screed against the Qadiriyya order’s archrival in northern Somalia, the Tariqa Salihiyya and its leader Sayyid Abdullah Hasan. Sayyidka, as he was known among Somalis, is most famous for the more than twenty-year insurgency he led against British and Ethiopian forces in northern Somalia from 1898–1920. But among Somalis he is also remembered for his long running feud with the Qadiriyya that ultimately led to the murder of al-Qutbi’s shaykh, Uways al-Barawi by followers of the Sayyidka in 1909. And, parts of the collection did, in fact, attack the Salihiyya as dangerous extremists who were no better than other heretics like the Kharijis, the Mu’tazilis and, worst of all, the Wahhabis.

Indeed, these elements of the text were the source of tension and even street-level violence when al-Qutbi took up temporary residence in the British port of Aden during the spring and summer of 1921 on his way from Cairo to Somalia. Stones were regularly thrown at the mosque where Shaykh Abdullahi preached, and there were a number of violent scuffles between Salihi and Qadiri adherents, apparently provoked by the book’s dissemination. As a result, British authorities declared it a threat to public order, seized at least 200 copies of the work and had them pulped. So, the image of al-Qutbi’s Majmu’a that has held sway for nearly a hundred years is that of a venomous tirade of only provincial importance. This view, however, overlooks the greater complexity of the work, and belies its engagement with the much wider world of Muslim reformist discourse in the early 1900s. In fact, the Shaykh’s condemnations of the Salihiyya take up surprisingly little of the book (only about 50 pages of a nearly 350 page work). The overwhelming bulk of the collection concerns itself with spiritual guidance and what one should believe rather than what one should not. The Somali hinterland of the early twentieth century was in many ways only lightly Islamized. The penetration of the Sufi orders into the interior dated only to the latter part of the nineteenth century, and if the writings of al-Qutbi and other oral accounts are to be believed, Muslim orthopraxy was hardly widespread. According to a number of sources, including al-Qutbi himself, un-Islamic practices such as alcohol consumption, mixed dancing and the blending of camels’ blood with milk as a dietary staple were rampant while regular prayer and fasting during Ramadan were hardly observed with any kind of rigor.

Ramadan were hardly observed with any kind of rigour. In response, much of the Shaykh’s essay Nasr al-Muminin, ‘Victory of the Believers’ – the longest of the four in the collection – was, in fact, a primer on proper religious belief and behaviour. Here al-Qutbi devotes himself to educating the faithful on a variety of matters. These include both the zahir or external elements of religion as well as the batin, the internal components of one’s faith. With regard to the former, for example, the Shaykh provides an extensive discussion of personal behaviour ranging from proper comportment when in a mosque, ethical business dealings and table manners to the permissibility of coffee, qat and alcohol (the first two are acceptable, while the last is not). With regard to the batin, he offers a lengthy discourse on the avoidance of sin and seeking the guidance of the saints (awliya’) and one’s shaykhs as the only sure path to developing the purity of a believer’s soul. It is within this same spirit of guidance that we find al-Qutbi’s discussion of taqlid, oddly paired – or so it would seem at first glance – with the subject of takfir or apostasy. And it is within this discussion, in particular, where we observe the shaykh’s ability to address multiple, disparate audiences such as the scriptural reformists, whose teachings he views as a mortal threat to the souls and well-being of his other audience, the average Somali believer.

Taqlid and takfir

There are probably few terms within Islamic reformist discourse that carry more baggage than taqlid. Commonly glossed as ‘blind imitation,’ the follower of taqlid (the ‘muqallid’) is frequently characterized as backward, lacking in imagination and reactionary for their perceived unquestioning adherence to the corpus of medieval jurisprudence and theology and refusal to employ ijtihad or individual reason in matters of law and theology. Contemporary scholarship has tended to privilege this view promoted by various reformist voices ranging from Muhammad ibn Ali al Sanusi to Muhammad Abduh and Rashid Rida while ignoring the writings of the term’s proponents such as Shaykh Abdullahi.

Recent scholarship has greatly enhanced our understanding of the term taqlid within classical Islamic discourse. Rather than a backward institution aimed solely at guarding the power and authority of the `ulama, scholars, Sherman Jackson and Mohammed Fadel have demonstrated its role in creating a kind of ‘positive case law’ in the latter part of the middle ages which was, in fact, a supplement to, rather than a substitute for, ijtihad (individual reason). Wael Hallaq has gone even further, declaring that taqlid constituted its own creative act with jurists invoking their own careful reasoning and intellectual independence when reproducing the opinions of the founders of jurisprudence. Legal decision-making, he notes, was anything but ‘blind'.

Taqlid, however, also functions outside the field of jurisprudence as an important theological concept. Richard Frank, in particular, has explored the important role of taqlid in Ash’ari kalam or ‘systematic’ theology, which teaches that the ‘unquestioning acceptance’ of the word of others – that is, ‘imitation’ – in recognition of God’s indivisible nature (rather than arriving at this conclusion via one’s own logical reasoning) is viewed as a serious – if not completely insurmountable – impediment to the purity of an individual’s faith.

Rather than a simple-minded evocation of ‘tradition’, taqlid, in the writings of al-Qutbi was a complex idea that encompassed both the legal and the theological. In the Majmu’a al-mubaraka the shaykh draws on the early roots of both uses of the term with a number of apparent goals. As a didactic text, al-Qutbi sought to provide guidance to his fellow Somali Muslims and put their minds at rest regarding issues surrounding proper conduct and belief. At the same time, it constituted a foray into the wider arena of reformist discourse. He accomplished both of these goals via the discursive tradition of Islamic theology. By drawing on various foundational medieval and early modern works of the Muslim theological canon, al-Qutbi was able to carve a clear path of guidance for his followers in order to help them navigate an increasingly complex spiritual world, at the same time establishing a presence in the reformist debates of the wider Muslim ecumene. Shaykh Abdullahi’s discussion of imitation and apostasy is a modest section of five pages in which he covers both the juridical and theological meanings of the first term over the first two-thirds of the section while sliding seamlessly into a discussion of the latter (takfir) in the last third. The logic that connects the two is made apparent only as one reads the section as a whole. What follows first is an overview of the section itself, highlighting the salient points. Following that, we will engage in a deeper discussion of its significance partly within the context of the Majmu’a, but more importantly within the wider framework of Muslim intellectual discourse in the early twentieth century. Shaykh Abdullahi was certainly aware of, and a proponent of, taqlid in its juridical sense. ‘Taqlid,’ he wrote:

is required and no one is permitted to foreswear it in these times because the unrestricted mujtahid [an individual of sufficient learning and moral standing, who is permitted to arrive at legal decisions independent of precedent] was discontinued long ago.

‘As our `ulama said,’ al-Qutbi wrote, ‘imitation is incumbent upon those who are not qualified to carry out [unrestricted independent reason], and must remain within one of the four prescribed [Sunni legal schools] … ’ In keeping with the didactic tone that pervades most of the text, al-Qutbi provides a very brief summary of the best way to practice juridical taqlid. Rather than a slavish following of tradition, however, what he lays out constitutes long established legal practice. In practicing ‘legal imitation’ an individual has three options, he notes. Option one is that followed by the most pious, and involves being ‘cautious’ and observing the strongest prescription found among the four madhhabs (or Sunni schools of law). For example all of the schools require the washing away of sperm after intercourse because it is unclean. But Shafi’i also requires ‘the washing away of urine because it is [similarly] unclean.’ So, if one strives to do ‘the most perfect thing in all circumstances’ – al-Qutbi enjoins his readers – one should ‘foreswear the [weaker] prohibitions,’ offered by other schools. Option two represents a middle ground, ‘in which it is incumbent upon an individual to follow a single madhhab [or school of law] and not diverge from it.’ This is the path, he notes, that most people follow and is perfectly acceptable. Finally there is the third, and least judicious alternative, seeking out and accepting ‘the easiest [opinion] from among the law schools,’ something that al-Qutbi advises the reader is inadvisable and of dubious legality. This discussion of what we might term ‘legal’ or ‘juridical’ taqlid, however, is surprisingly brief. As al-Qutbi points out, there are, in fact two kinds of taqlid, ‘taqlid as in the branches of jurisprudence and taqlid in the proofs of tawhid [God’s indivisible nature].’ It is the latter the shaykh viewed as far more important and which takes up the majority of his discussion.

Theological taqlid, he notes is:

the acceptance of the teaching of another without knowing its logical proof [a formula demonstrating the assertion’s truth]. Rebellious is the one whose faith is that ensured by another, and rebellion contains unbelief as does taqlid … without knowing its logical proof

While ‘imitation’ in matters of the law was laudable and necessary, it was a different matter when it came to one’s faith in God and the notion of His indivisible nature or tawhid. ‘Taqlid in [matters] of the unity of God and doctrine,’ he writes, ‘is not permitted to the Muslim … ’ Instead, according to ‘the Imams of Kalam’ a true believer must have ‘perfect knowledge’ of God’s oneness, ‘[arrived at by] deliberate reasoning [or logical proofs].’ Citing one of these ‘Imams of theology’, al-Qutbi writes, ‘if faith is an imitation, it is not free from indecision and confusion,’ as the author of the Jawhara al-tawhid [Abd al-Salam Laqqani] said,

Whoever follows blindly with regard to the Oneness of God His faith is not free from doubt

The ‘Imams of Kalam’ to whom al-Qutbi refers were the fathers of Ash’ari theology, a medieval school of thought associated with Abi al-Hasan al-Ashari (d.936). The Ashari’s argued that for every believer to exhibit true, sound faith it was incumbent upon them to arrive at an independent knowledge of God via the use of certain logical formulas or ‘proofs’ (dalil or burhan) rather than simply accepting the statements of others at face value. Among `ulama in nineteenth and twentieth century East Africa, the Ash’ari School was the most influential and widely followed theological school. In line with the early Ash’aris, al-Qutbi writes that ‘whoever blindly imitates the Qur’an and the Sunna, his faith is not one positively arrived at [qata’i] and whoever [simply] imitates other than these, his faith is not sound.’ So, while juridical taqlid was laudable and, indeed, necessary, theological taqlid laid the groundwork for an imperfect, defective faith and should thus be abjured. As al-Qutbi reveals, however, the need to avoid theological taqlid was not necessarily as categorical as it might first appear. Following this seemingly categorical statement on the necessity of shunning imitation, the good Shaykh began to backpedal. Al-Qutbi argued that while mastery of the proofs was ideal it was not necessarily practical for all believers. As such, he noted, there existed certain loopholes.

The pure whose heart is filled with faith, [but] who is incapable of executing the proofs of God’s unity and imitates what is generally accepted … he is among the faithful, because he is not [one of] mere opinion [zann], because his belief conforms to the evidence

In other words, while it is ideal to attain mastery of the Proofs of God’s indivisible nature, there was a realization that not all believers possessed the intellectual ability to do so, and as such a certain amount of imitation was both inevitable and permissible. There were those, he noted, who held that whoever was a muqallid [an imitator] in this regard was guilty of unbelief. Al-Qutbi noted that the North African theologian Muhammad b. Yusuf al-Sanusi (d.1490) declared ‘the muqallid commits unbelief in religious dogma and he is deficient.’ Shaykh Abdullahi argues, however, that while this may be the case when one is before God in ‘the other world,’ in this one ‘whoever recites the shahadatayn [the profession of faith], he is a Muslim.’ Al-Qutbi was not out of step with classical Ash’ari teachings that made similar declarations. So, to support his case, the shaykh turned to one of the medieval pillars of Asha’ri thought, ‘Abd al-Salam Laqqani (d. 1041 or 1078) and his Jawhara al-Tawhid. Laqqani, you may recall was the scholar we heard declare earlier ‘Whoever follows blindly with regard to the Oneness of God/His faith is not free from doubt.’ However, Shaykh Abdullahi notes that within the course of the same work, Laqqani qualified this, stating ‘whoever establishes and takes upon himself Islamic principles in this world cannot take on unbelief unless he commits it [specifically] by word or action such as bowing down to idols.’ The Ash’ari father, al-Qutbi tells his readers, was not alone in this view. According to Ibn Hajar:

In the last Hadith of Jibril it says ‘Know! It is obligatory to have faith in God, His angels, His Books, His Messenger and the Day of Judgement, it is not obligatory to contemplate the logical proofs to have definitive belief.’ – it is possible to be dogmatically sound as long as one chooses to follow the salaf (lit. the pious ancestors or forefathers,) the Imams and the jurists, [if one does this] the faith of the muqallid is sound.

In short, a believer is obligated to utilize the proofs of faith unless he or she does not possess the intellectual wherewithal, in which case it is acceptable to follow the example of a venerated shaykh. ‘The muqallid,’ al-Qutbi sums up uncategorically, ‘is an acceptable Muslim as long as he follows the shari’a muhammadiyya [the law of the Prophet] like the majority of believers.’

In the stream-of-consciousness that is al-Qutbi’s writing style, the discussion shifts at this point to the question of takfir or the commission of ‘unbelief.’ The Shaykh states that there are those who argue that to not know the logical proofs of tawhid is to commit unbelief. On the other hand, there are others who regard the act of ‘philosophical speculation’ (Ar. kalam) as forbidden. So, what is a pious believer to do? Such utterances al-Qutbi contends are nothing but ‘preposterous ravings.’ With regard to the former, he reiterates the notion that those who do not know the proofs need only follow the Qur’an, the Hadith/Sunna and shari’a in order to remain faithful believers. By the same token, those who ‘teach that the salaf forbid philosophical speculation’ because ‘ilm al-Kalam was not taken up by them’ are in error, ‘as is their forbidding of the knowledge of the Qadiriyya’ and their criticism of ‘al-Shafi’i and others from among the pious ancestors.’

The greatest sin committed by both parties is the reckless manner in which they throw around the term ‘unbeliever.’ Al-Qutbi laments the fact that there were far too many in his day and age who were quick to accuse others of committing takfir, apostasy. This, he declared, was simply contrary to the spirit of the faith. The sayings of the Prophet, he tells his audience, declare ‘whoever says to his brother Muslim, ‘ya-Kafir’ it comes back on the them.’ and that the faithful should avoid declaring ‘anyone who is from the people of the Qibla [those who kneel in prayer towards Mecca] an unbeliever,’ without explicit evidence. Unbelief, he concludes, may only result from ‘word, deed or belief,’ indeed, ‘the jurists’ might discuss it in great detail, ‘but there is nothing here other than warnings against making charges of unbelief.’

Abdullahı - al-Qutbi and the discursive tradition

It would be easy to dismiss this section of al-Qutbi’s work as theological esoterica aimed solely at a narrow scholarly audience. Certainly, as we will see in a moment, it was intended to refute particular contemporary currents of religious reform. But it was also aimed at a less scholarly audience – al-Qutbi’s fellow Somalis – in the hope of helping them navigate the ever-shifting parameters of acceptable belief that characterized the early twentieth century. The discussion of taqlid and takfir (along with other sections such as the author’s discussion of kafa’a or marriage equivalence not discussed here for reasons of space) reveals much not only about al-Qutbi’s intended audience but the nature of religious dialogues during this period.

The era in question was one increasingly dominated by those we might refer to as ‘scripturalist reformers’ such as Rashid Rida who held that the only acceptable sources of spiritual guidance were the Qur’an and the Hadith of the Prophet Muhammad as mediated by his early followers. Those who looked to other, generally later, guides – such as the founders of the four Sunni law schools or the Asha’ri fathers – were deemed to possess a faith that was weak if not outright defective. Today, many tend to lump these various voices rather uncomfortably and anachronistically together as ‘Salafis’ (the followers of the Salaf al-Salih, or the ‘pious ancestors’). Al-Qutbi’s writings were a response to these scripturalist reformers. In addressing both audiences, al-Qutbi looked to his own theological predecessors and the Asha’ri canon to counter those he refers to as ‘innovators’ [mubtadi’] and provide guidance to the common faithful.

Al-Qutbi’s reformist audience and the discursive context

The evidence pointing to al-Qutbi’s intention to engage with the higher levels of reformist debate is somewhat circumstantial, but I believe, on balance, weighty enough to be convincing. First, is his very presence in Cairo during and after the Great War. Egypt in general, and al-Azhar in particular, was an epicenter of the debates surrounding Islamic reform in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, reaching a fevered pitch in the period immediately following the war. The notion that al-Qutbi would not have been influenced by such debates while studying there is diffi- cult to imagine. Furthermore, his choice of publisher suggests a more than passing familiarity with the ideological fault-lines of the period.

By 1900, Cairo was regarded as a capital of Arabic printing and book production. The adoption of print came relatively late to the Middle East and most Islamicate lands. The reasons for this are complex and continue to engender debate. Large scale production of printed matter was first introduced by the Pasha Muhammad Ali in the early nineteenth century when he established a government printing house at Bulaq. The output of this press was extremely limited, and it was not until the middle of the century and the introduction of lithographic technology that printing became widespread. Cheap print led to the rapid development of a lively print culture in urban Egypt with literally dozens of small firms, mainly in Cairo and Alexandria, producing an eclectic array of books, pamphlets and newspapers for the consumption of a growing reading public. Concentrated in the area of ‘old’ Cairo around the Khan al-Khalili and al-Azhar, a few of these, such as the Maktaba al-Salafiyya established in 1909, were founded to serve a particular ideological agenda, in their case scripturalist reform. Most, however, were small shoestring affairs that subsisted largely by printing what they judged the public wished to read and producing works on commission. It was to one of these latter firms Abdullahi al-Qutbi turned to publish his masterwork.

The area around al-Azhar in the early twentieth century was surrounded by these small ‘boutique’ publishing firms that specialized in running up quick, cheap editions of works brought to them by the growing international community of students and scholars resident at the university. These might include scholarly commentaries, collections of sermons, mystical poetry or hagiographies of local saints among many other texts. To publish his collection, Al-Qutbi chose one of the most prominent of these, Mustafa al-Halabi & Sons. Founded around 1859, Halabi & Sons was a commercial publisher that, like most, operated on a commission basis. By 1919, however, it was a firm with a growing reputation for publishing a wide variety of Sufi related texts and other works that were often implicitly, if not explicitly, opposed to the growing trends of literal-minded scripturalist reform. They appear to have been the publisher of choice for Somalis as well as pro-Sufi, anti-scripturalist elements from East Africa and Aden to Southeast Asia. Given the many options one had surrounding al-Azhar, it would seem that Shaykh Abdullahi was making a very deliberate statement with his choice of publisher.

There also exists a certain amount of evidence within the texts that points to the shaykh’s intention to engage with ideas that were not of a purely local nature. For instance, al-Qutbi was rarely shy about specifically singling out the Salihiyya and ‘their sayyid,’ his principal local opponents as the purveyors of bid’a – or unlawful innovation – in many places throughout his text. In the section on taqlid (as well as the one on Kafa’a), however, the Salihiyya are conspicuous by their absence. In the section on Kafa’a or‘equivalence in marriage’ al-Qutbi refers to his adversaries simply as‘the innovators’ who ‘pretend not to know the proper kafa’a in marriage,’ and so endorse various kinds of socially inappropriate marriage alliances, such as that between ‘free and slave.’ In the section on taqlid, he generically points a finger at those who contend ‘‘ilm al-kalam is an unlawful innovation.’ In neither section are the Salihiyya mentioned explicitly. The position of Sayyid Abdullah Hasan on kafa’a is not clear (we’re not even sure if he addressed it); however, there is at least some evidence in his writings that he subscribed to Asha’ri theology, and so could not convincingly be lumped in with the enemies of kalam or be labeled a scripturalist reformer.

Finally and most importantly, at the end of al-Qutbi’s book there are two curious endorsements. The first was by a certain ‘Umar b. Ahmad al-Somali, a shaykh resident at al-Azhar who praises the anti-Salihiyya aspects of the text as one might expect. The other was by Yusuf b. Isma’il al-Nabhani, a Levantine ‘alim who was one of the most prominent and vociferous anti-scripturalist voices of the early twentieth century. Nabhani’s endorsement is worth quoting at some length:

I must speak [on behalf of] this book which is one of the best religious books written in our age … it will be of great benefit to Muslims, bringing to them guidance sufficient [to counter] the mischief of the envious and the innovators,

for this, he concludes, al-Qutbi would surely earn the love of the Prophet. Based on this, it would seem clear that at least one influential reader viewed al-Qutbi’s work as a new weapon in the struggle against ‘innovating’ scripturalist reformers, wherever they might be.

Given al-Qutbi’s apparently self-imposed exile at al-Azhar, his engagement with emerging scriptural based reform-minded discourse is hardly surprising. However, there is actually a more important insight to be gleaned from his work that centers on al-Qutbi’s desire to act as a guide for his fellow Muslims through the turbulent waters of reform in the early twentieth century utilizing the corpus of Islamic tradition.

In her book Reconfiguring Islamic Tradition, Samira Haj examines the work of the important nineteenth-century Egyptian reformist thinker Muhammad Abduh as part of a dynamic tradition which called upon a ‘corpus of Islamic knowledge,’ in order to respond to contemporary challenges. Drawing on the work of Talal Asad and Alasdair MacIntyre regarding the nature of ‘tradition,’ Haj argues that while scripturalist reformers of the period looked to an ideal of the Islamic past for inspiration ‘tradition is not simply the recapitulation of previous beliefs and practices; rather each successive generation,’ uses it to ‘confront [and remedy] its particular problems.’ Recourse to ‘tradition’ as a remedy for the ills of the present I would argue was hardly a monopoly of such reformers.

Shaykh Abduallahi was himself the representative of a reformist tradition in Somalia and, indeed, East Africa more broadly. As I have discussed elsewhere, from the latter decades of the nineteenth century adherents of various Sufi turuq or brotherhoods, such as al-Qutbi’s Qadiriyya order, effectively missionized the Somali interior in an effort to replace certain local traditions with their own orthopraxy. In particular, they sought to convince the Somali herders of the interior to shun certain long established social customs such as blood drinking and mixed dancing in favor of more acceptable ritual practices such as observance of the five pillars, remembrance of the ‘awliya through dhikr and proper ritual slaughter. By Shaykh Abdullahi’s generation, according to most accounts, the brotherhoods had experienced remarkable success, and a large proportion of the population looked to Sufism as the primary rubric for defining and understanding their faith.6

However, the world for Somali Muslims at the start of the twentieth century was a place of spiritual uncertainty. At home, there was doctrinal strife and a bloody insurgency. Abroad, in ports like Aden and Suez – where many Somali men had ventured to find work as policemen, stevedores, stockmen and sailors – they were exposed to the blandishments of reformist preachers who derided those who subscribed to the cult of the saints or professed Asha’ri belief as ‘vile imitators’ or, even worse, kuffar (unbelievers). As a widely traveled ‘alim, al-Qutbi was well aware of these travails, and his work can, at least in part, be read as an attempt to provide both guidance and succor to his audience utilizing the faith’s corpus of tradition.

Based on what we know of the shaykh’s movements via the colonial record, it seems evident that his work was a didactic text intended to minister to the souls of believers in those troubled times. We know that he returned to Somalia via the British controlled towns of the Suez Canal and Aden. In the latter, he spent several months teaching and preaching in a local mosque. As noted earlier, the British impounded and destroyed upwards of 200 copies of the Majmu’a in Aden. However, the Resident in British Somaliland reported when al-Qutbi arrived back in the Horn of Africa some months later, he proceeded inland with a small caravan of pack camels laden with copies of the text he had had the foresight to deposit in the Somali port of Zeyla. As the shaykh traveled back to his natal home, he taught, preached and gave away copies of the text to local teachers with a knowledge of Arabic who could then ensure the lessons he wished to impart would survive. But, what were these lessons? Taken at face value, al-Qutbi’s discussions of theological taqlid and takfir are esoteric at best. However, reading across the discussion of frequently arcane points of theology, we find that the shaykh was remarkably consistent on one point – his constant reassurance to his readers that as long as they were moral and sincere believers, they would not stray from the true path.

There exist those, he notes, who were quick to declare others ‘unbelievers.’ These were the same unnamed people who held that ‘the salaf forbade philosophical speculation,’ that the teachings of the Qadiriyya were illicit and even dared to criticize Imam Shafi’i and ‘others among the pious ancestors,’ labeling all who followed them ahl al-bid’a (followers of unlawful innovation). Al-Qutbi reassured his readers that they had nothing to fear from those who ‘transmit hypocrisy, quarrels and specious arguments.’ Unbelief, he noted more than once, was not something with which an individual could be labeled, but could only happen through the commission of a deliberate, rational act. Unbelief could only result from ‘word, deed or professed belief.’ Those who threw around accusations of unbelief ran the risk of committing it themselves.

But even if one could not be deemed an unbeliever, in an increasingly complex world how could a person be sure he was following the right path? Al-Qutbi’s answer to this was simple, and drew on the length and breadth of Muslim tradition, in particular the writings of the Asha’ri scholar Abd al-Salam Luqqani. Shaykh Abdullahi reminds his readers that, ‘whoever recites the shahadadatayn [the profession of faith,] he is a Muslim.’ While some scholars may disagree with this point and consider one who practices taqlid a ‘deficient’ believer, the Asha’ri fathers, al-Qutbi pointed out, would beg to differ. Quoting and paraphrasing alLuqqani, al-Qutbi notes that ‘the faith of the muqallid when based on the judgments of another … in this world and [if he is] of sufficient faith is sound.’ Furthermore, ‘the muqallid is an acceptable Muslim’ as long as he follows the Law of the Prophet like all other believers.

Although clearly a discussion of theological taqlid, al-Qutbi was in fact encouraging his readers to look towards their religious leaders for guidance, ‘it is not obligatory to contemplate the logical proofs to have definitive belief, it is enough to … follow the salaf, the Imams and the jurists. If one does this, the faith of the muqallid is sound.’ 69 Shaykh Abdullahi al-Qutbi’s Majmu’a al-mubaraka is representative of the connectivity of African Muslims with the larger umma across both space and time that has been in evidence since the faith’s arrival – the notion that began this essay. We see through his writings that even a local ‘alim from the remote Somali interior could engage – across space – with the dominant discourses of reform of his age and do so – across time – utilizing the discursive tradition. This was a connectivity, however, that had become more rapid and pervasive with the rise of European empire and ‘the age of steam and print.’ Because, of the ubiquity of steam travel and the dissemination of knowledge made possible by cheap print, Somali Muslims were interacting with a wider swath of believers and ideas than ever before. While the Majmu’a illustrates the interpenetration of the global and the local thanks to new technologies, al-Qutbi demonstrates that the encounter was not always a smooth one. Global discourses of reform were increasingly present in the lives of believers, but al-Qutbi’s writings uncover the continuing centrality and legitimacy of local authority in the propagation of Islamic teachings. At the same time, the fact the Shaykh could use the same text to speak to very disparate audiences reveals the coherence and connectivity of that intellectual universe.

In the end the Majmu’a was intended to distill the debates of the age for believers and, at least in part, provide moral guidance through this world of uncertainty. Cloaked in a veil of difficult to digest theology, al-Qutbi carefully reminds his fellow believers that while the world around them was indeed complex and fraught with peril, all one really needed to do was to remain pious and try to live a good life in accord with divine law. As for the rest, they need only follow their shaykh, and his example would guide them to the ‘proof’ of their faith."

References

You don't have permission to view the spoiler content.

Log in or register now.

I thought this was only the Masaai.

I thought this was only the Masaai.