You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Rome empire trading with somalis

- Thread starter Nin123

- Start date

I used to think "Barbar" came from "Barbaros/Barbaroi" like what they called the Germanic tribes in Europe but it seems more likely they were extrapolating a Nubian ethnic term onto us similar to how they took the label "Arab" and used it for various regions of the peninsula:

Barbar's likely origins

What I find personally very interesting about the Greek and Roman descriptions of the Cushitic speaking coasts of NE Africa is how similar things look to the Early Modern Era and ostensibly also the Middle Ages; a collection of port-towns largely independent from each other, each ruled by its own "Chieftain" who were probably those days' equivalents of the Medieval and Early Modern Garaads, Suldaans, Ugaasiin and so on. Somalis and other Cushites were always fairly decentralized, I would argue.

Barbar's likely origins

What I find personally very interesting about the Greek and Roman descriptions of the Cushitic speaking coasts of NE Africa is how similar things look to the Early Modern Era and ostensibly also the Middle Ages; a collection of port-towns largely independent from each other, each ruled by its own "Chieftain" who were probably those days' equivalents of the Medieval and Early Modern Garaads, Suldaans, Ugaasiin and so on. Somalis and other Cushites were always fairly decentralized, I would argue.

Bro you have so much information and i enjoy your threads especially on diets and Somali history ones.I used to think "Barbar" came from "Barbaros/Barbaroi" like what they called the Germanic tribes in Europe but it seems more likely they were extrapolating a Nubian ethnic term onto us similar to how they took the label "Arab" and used it for various regions of the peninsula:

Barbar's likely origins

What I find personally very interesting about the Greek and Roman descriptions of the Cushitic speaking coasts of NE Africa is how similar things look to the Early Modern Era and ostensibly also the Middle Ages; a collection of port-towns largely independent from each other, each ruled by its own "Chieftain" who were probably those days' equivalents of the Medieval and Early Modern Garaads, Suldaans, Ugaasiin and so on. Somalis and other Cushites were always fairly decentralized, I would argue.

What are the odds that we find manuscripts if we excevate these small collcetions of port towns. I've thought for a long time that there has to be some written tradition. Considering how I've read papers that use somali poetry as evidence that the gap ortature and written literature is blurry. I also read sade mure 2018 paper and zhe mentions a significant amount of Christian burials and at the end she makes an offhand comment about ge'ez manuscripts found. Both of these things the similarities of our poetry to poetry from written literatures and the existence of these port towns and possible ge'ez manuscripts on top of the sumado . Make me think there is a high possibility we had a written tradition and it'll most likely be found around these port towns or in the Christian cairns. Maybe we'll even find a somali Bible translated from ge'ez

What are the odds that we find manuscripts if we excevate these small collcetions of port towns. I've thought for a long time that there has to be some written tradition. Considering how I've read papers that use somali poetry as evidence that the gap ortature and written literature is blurry. I also read sade mure 2018 paper and zhe mentions a significant amount of Christian burials and at the end she makes an offhand comment about ge'ez manuscripts found. Both of these things the similarities of our poetry to poetry from written literatures and the existence of these port towns and possible ge'ez manuscripts on top of the sumado . Make me think there is a high possibility we had a written tradition and it'll most likely be found around these port towns or in the Christian cairns. Maybe we'll even find a somali Bible translated from ge'ez

I knew a Jewish Afro-Asiatic linguist who seemed surprisingly certain that the Somali coast inhabitants of these port-towns were familiar with writing. They had to be. We've found Musnad inscriptions in the ruins and these were people trading with Greeks, Romans, Indians, Arabians... all peoples familiar with writing. They at the minimum would have seen others using writing. The only step remaining would be if they'd see a need to adopt it themselves. Given how quickly Somalis seem to have adopted Arabic as a writing system and also as a written language in many cases I suspect he was correct and they probably did adopt something or other back then; probably Musnad.

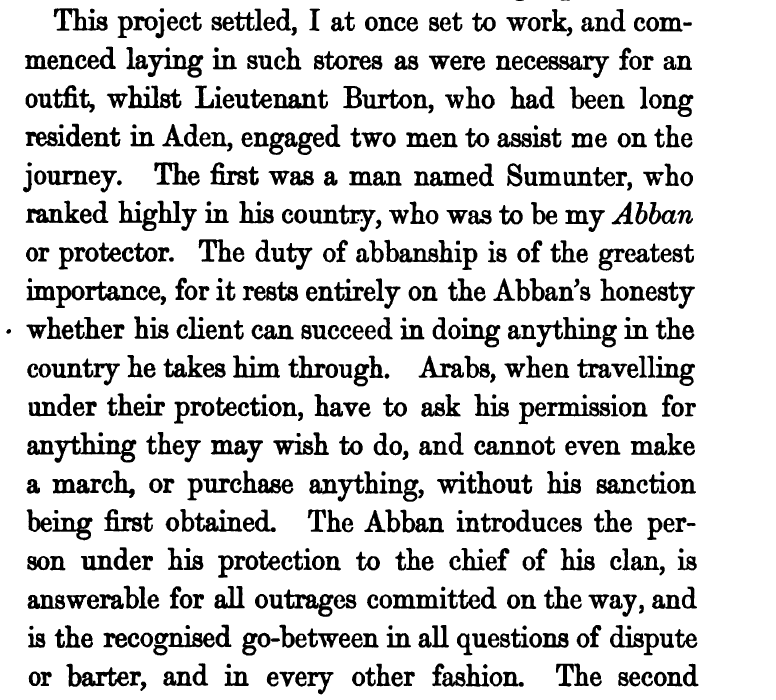

I actually showed him some of Sada Mire's Musnad inscriptions and he pointed out to me that some of the symbols did not look right or like Musnad symbols he knew which is interesting. And it's also very interesting where some inscriptions pop up; the interior of the country. Why is this important? Well, simply put, the system of Abbanship:

Somalis literally always had a system of sponsorship and monitoring with ajanabis. If you came onto a coastal town from both Woqooyi to Koonfur you had to be given a local Somali "Abaan" which people like Burton and Speke describe and even Ibn Battuta basically describes. Your abaan keeps an eye on you, takes a certain cut of all your business transactions and is usually also tasked with making sure you do not go into the interior of the country without express permission from someone like a local Suldaan and even after that the Abaans were always very suspicious of ajanabis and watched them closely. Our ancestors were very suspicious of letting ajanabis onto their lands. I've seen accounts that show Indians who settled in places like Xamar basically would spend their entire lifetime in the magaalad inside its walls. Never venturing into even Afgooye.

This is probably a big reason why we weren't really enslaved historically. Not just a matter of being Muslims but also being very cautious with foreigners and not letting them wander the interior where they can kidnap rural women and kids.

- Source

For almost 600 years between the time Ibn Battuta came to Xamar to when cadaans were running around Woqooyi and Bari, this system seems to have existed among Somalis and given the intriguing continuity of so many customs going back hundreds to thousands of years, I'm willing to bet this one existed 1,500 to 2,000 years ago. What this simply means if true is that it wouldn't be possible for people from Yemen to make their way deep into the interior of Somali country and leave inscriptions all over the place on random boulders, in caves and so on. So it had to be natives... and perhaps a similar situation to Arabians where more people than usual were familiar with literacy, contrary to popular belief regarding the era of jahiliyya:

For starters, I am somewhat of the opinion that cadaans authors were a little blind to the fact that while most Somalis, like most pre-modern people, would have been illiterate, many were arguably only functionally illiterate in that they knew how to read and write but not in a language they actually spoke and understood:

Link

Another very big hint is in muse galal book on astronomy and folklore. We have an incredibly complicated system of astronomy and astrology. In the book he talks about multiple metaphysical concepts like nuro,nabsi,and naqsi that somalis believed in. But what stood out to me the most is that he mentions we monitored the moon through 28 stations.which struck me as very simialr to the chinese 28 mansions which are about the movements of the moon. I tried to find parallels in other african culutres understanding but I couldn't find anything remotely similar. You also have to understand this was extremely widespread its referred in the sayyids poetry and apocryphal saying of arawelo. We also know that it's old because those state horn project guys had somebody check if the xiis cairns aligned with the calendarical system and they found that these 3rd century graves somehow aligned.

Another very big hint is in muse galal book on astronomy and folklore. We have an incredibly complicated system of astronomy and astrology. In the book he talks about multiple metaphysical concepts like nuro,nabsi,and naqsi that somalis believed in. But what stood out to me the most is that he mentions we monitored the moon through 28 stations.which struck me as very simialr to the chinese 28 mansions which are about the movements of the moon. I tried to find parallels in other african culutres understanding but I couldn't find anything remotely similar. You also have to understand this was extremely widespread its referred in the sayyids poetry and apocryphal saying of arawelo. We also know that it's old because those state horn project guys had somebody check if the xiis cairns aligned with the calendarical system and they found that these 3rd century graves somehow aligned.

Yes, I'm aware of this and found it quite interesting but isn't it also true that Oromos and other East Cushites had similar calendrical systems or were theirs less complex? That being said, I showed that linguist this, for example:

One of the early inscriptions Sada Mire made public. And he said it didn't actually look like any Musnad he knew. And I trust this guy because Semitic is his specialty yet despite that he is so well-versed in the rest of AA that he reads Hieroglyphs to people at museums as a party trick. Kekekeke. Very knowledgeable. I couldn't believe it fully even so hence I looked up the Musnad letters:

𐩠 h

𐩡 l

𐩢 ḥ

𐩣 m

𐩤 q

𐩥 w

𐩦 s² (š)

𐩧 r

𐩨 b

𐩩 t

𐩪 s¹ (s)

𐩫 k

𐩬 n

𐩭 ḫ

𐩮 ṣ

𐩯 s³ (ś)

𐩰 f

𐩱 ʾ

𐩲 ʿ

𐩳 ḍ

𐩴 g

𐩵 d

𐩹 ḏ

𐩻 ṯ

𐩼 ẓ

The one farthest to the left could be "q" if the shadow is obscuring another line under the "O" but he's seemingly right about the other 3 symbols. That does not actually look like Musnad. I wonder if Sada Mire just assumed this was OSA cos I'm not seeing it. Are you?

Last edited:

I mean wallahi that's very possible. I don't think she is trained in semetic languages. Plus we know from the temple inscriptions excavated in 2019 that there were people on the somali coast with knowledge of musnad in the 7th century b.c.e . So of course they would have based their script of musnad. We might actually be looking at the first inscription of proto somali. On top of the fact that we have loan words from old south arabian so somebody could easily mistake it as illegible sabean inscriptions. There also has to be connection with sumado somewhere since some of the symbols look similar.

Oh and on the calendrical systems. I haven't seen anything written except on the borana and their ritual system. There must of course be similarities. But I suspect like how are poetry has no real parallels in other cushitic languges it seems to their are no similarly advanced calendrical systems. Since it would have merited A mentione somewhere just like how they mention gadaa and oromo folk songs when they tall about their oral traditions

I mean wallahi that's very possible. I don't think she is trained in semetic languages. Plus we know from the temple inscriptions excavated in 2019 that there were people on the somali coast with knowledge of musnad in the 7th century b.c.e . So of course they would have based their script of musnad. We might actually be looking at the first inscription of proto somali. On top of the fact that we have loan words from old south arabian so somebody could easily mistake it as illegible sabean inscriptions. There also has to be connection with sumado somewhere since some of the symbols look similar.

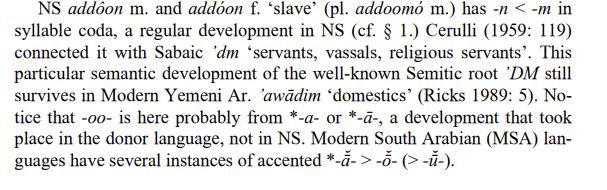

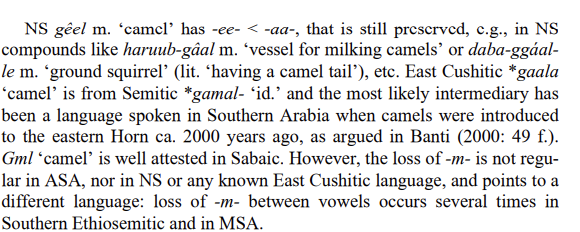

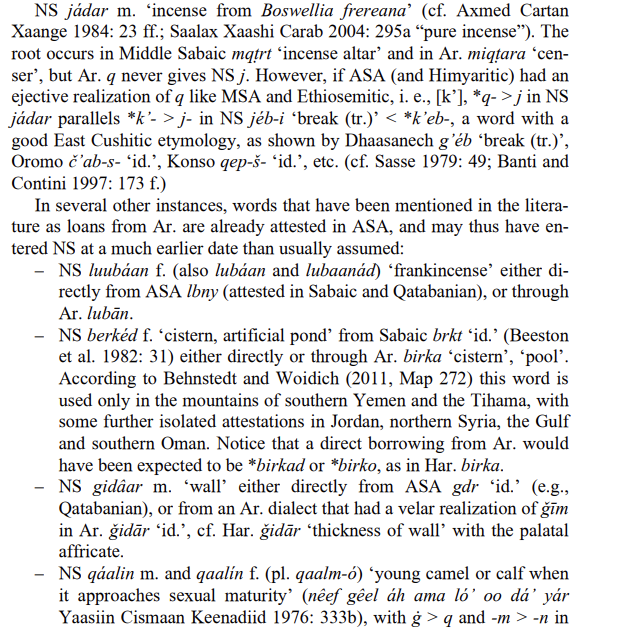

The loanwords from OSA themselves are very telling:

Source

They're all blatantly trade-related. Camels, frankincense, slaves... all things they likely exported to us and vice-versa. We were in business with these people and if there were port-towns with "Chieftains" (i.e. Garaads) presiding over them then these fellows would have, exactly like the Early Modern Era, no doubt wanted to keep records of their possessions. The wells they controlled, the portions of grain, dates and the numbers of camels under their control and probably also send letters back and forth between themselves and the rulers on the Yemeni side of the coast like in the Early Modern era. It would be a little weird to be in bustling business with so many peoples (Indians, Romans, Greeks, Arabs etc) without some amount of record and law-keeping the way the qadis and wadaads used to do it for the Suldaans just a century ago. I kinda see that linguist's point when I think about it like this.

In fact, the funny thing is, this is literally how writing arguably originated in parts of the fertile crescent; elites wanting to keep records of what was collected through taxation, for example.

I saw an artefact people we know found on their land. It also contained a musnad looking script engraved on items and according to someone who knows ancient semitic languages it doesn't quite match what they would expect.

The ones found at Shal'aw do appear to be conventional musnad though maybe those were left behind by Sabean travellers.

I believe the Oromo do have a calender system of their own but no clue about how sophisticated it is.

I am convinced if a group crowdfunded those cool aerial radar drones archaeologists use to find ruins under the ground and aims at the most suitable sites we would find so much under the ground. Somalia has got to be of the easiest places to lose heritage sites on Earth.

This is happening in Hobyo now a number of villages have already been swallowed. Imagine how much has disappeared in multiple millennia from this let alone ruins simply being destroyed by people reusing bricks.

www.voanews.com

www.voanews.com

The ones found at Shal'aw do appear to be conventional musnad though maybe those were left behind by Sabean travellers.

I believe the Oromo do have a calender system of their own but no clue about how sophisticated it is.

I am convinced if a group crowdfunded those cool aerial radar drones archaeologists use to find ruins under the ground and aims at the most suitable sites we would find so much under the ground. Somalia has got to be of the easiest places to lose heritage sites on Earth.

This is happening in Hobyo now a number of villages have already been swallowed. Imagine how much has disappeared in multiple millennia from this let alone ruins simply being destroyed by people reusing bricks.

Sandstorms Swallowing Somali Coastal Town

Residents of Hobyo, Somalia, say drifting sandstorms are burying their homes, schools and shops and threatening the existence of the coastal town.

Last edited:

Yeah I've read this paper. Sabaic lingustics seems like a mess to me. Every word is attributed in one direction with us borrowing from them. I found it very hard to belive since we know that going back at least to the periplus that somalis were arriving at their coast. So the borrowing could easily be in the other direction. Plus I'm very skeptical of any borrowing from southern ethiosmetic into somali. On top of the biggest mystery of all which is where the hell did the modern south arabian languges come from theri not decsended from old south arabian maybe a possibel cushitc semetic creole ?

There was a linguist who spoke of a 'Cushitic sub-stratum' in the Peninsula- I can't remember what his name was.

I remember seeing genetists saying that Mehri and other South Arabian are likely to be about 10% Cushitic DNA wise so this does seem to make sense.

I remember seeing genetists saying that Mehri and other South Arabian are likely to be about 10% Cushitic DNA wise so this does seem to make sense.

Yeah to me the fact that you have modern south Arabians lanaguges which should clearly show descent from old south arabian but don't show how big the gaps are. One of my big hopes is that we discover a mini dunhuang of somali manuscripts. One thing that's obvious if your read the research done on somali cairns. Is that some of the grave goods found match those found in royal aksumite and meroe tombs. It obvious from this that these coastal somali ports were no joke and the idea that such wealthy somali merchants who also traveled to eygpt and the roman empire (somali dna found in serbia) to trade left behind no written material remnants seems impossible.There was a linguist who spoke of a 'Cushitic sub-stratum' in the Peninsula- I can't remember what his name was.

I remember seeing genetists saying that Mehri and other South Arabian are likely to be about 10% Cushitic DNA wise so this does seem to make sense.

Yeah I've read this paper. Sabaic lingustics seems like a mess to me. Every word is attributed in one direction with us borrowing from them. I found it very hard to belive since we know that going back at least to the periplus that somalis were arriving at their coast. So the borrowing could easily be in the other direction. Plus I'm very skeptical of any borrowing from southern ethiosmetic into somali. On top of the biggest mystery of all which is where the hell did the modern south arabian languges come from theri not decsended from old south arabian maybe a possibel cushitc semetic creole ?

The MSA languages are not descended from the OSA languages, no. Weird, I know. They should have maybe picked a different name, kekekeke. But they interestingly do have a Cushitic substratum, that appears to be legit. That same linguist I knew confirmed as much years ago as well. Yemen is also littered with the same ancient Cushitic rock-art as the Horn that begins to appear around 3000 BCE and ostensibly comes from the Sudanese Neolithic. This rock-art is found enough in Yemen that some scholars call it the "Ethiopian-Arabian" style of rock-art or something to that effect. All most likely left by early Cushites. I lost the paper but about a decade ago a Tigrinya friend also showed me a study showing Horn to Yemen archaeological influences even after this in that Horner stelae culture also spread to Yemen. It was definitely not always a one-way street influence wise. Yemen seems to have possibly been Cushitic before the Semites came from the Levant and supplanted the earlier Cushites.

Then there's also the fact that, historically, despite how much people try to ascribe Arab origins and dominance to Somali port-towns it was historically Somalis who had a far stronger presence in Yemeni towns like Mukha/Mocha and Aden whereas any descriptions of Somali port-towns from 1300s to the 1900s mostly give you the impression that anyone "light-skinned" or outright recorded as Arab was a very small minority. I wish @Idilinaa was online. He had a lot of cool stuff about Somalis being in Yemen as far back as the 1400s-1500s that he showed me ages back where he convincingly showed, with scholars like Shidaad, that the people being called al-Jabarti or al-Zaylai'i running around Yemen back then were basically Somalis. But point is that Yemen to Horn influence didn't always go that way. As you know, the northern Xabashis literally once ruled a part of southern Yemen.

But that being said, MSA speakers are actually a very interesting bunch in that they seem to have maintained a system similar to Somalis during the Early Modern Period of using Arabic as their written and trade language in many cases then their own mother-tongue (i.e. Mehri) to speak amongst themselves. Though, if I'm not mistaken, unlike with Somalis there's not much proof of a tradition like Far Wadaad among them until very, very recently. They seem to have overwhelmingly used Arabic and perhaps also OSA in the past to write, though I'll do some more digging sometime.

Last edited:

I haven't seen this but presumably since it was a major port and most slaves were sold through somali Ports its definitely possible.What do they mean about trading slaves from opone? (Modern day hafun)

Yeah to me the fact that you have modern south Arabians lanaguges which should clearly show descent from old south arabian but don't show how big the gaps are. One of my big hopes is that we discover a mini dunhuang of somali manuscripts. One thing that's obvious if your read the research done on somali cairns. Is that some of the grave goods found match those found in royal aksumite and meroe tombs. It obvious from this that these coastal somali ports were no joke and the idea that such wealthy somali merchants who also traveled to eygpt and the roman empire (somali dna found in serbia) to trade left behind no written material remnants seems impossible.

Come again, niyahow? Please link! Please link! I've not been as up to date with pop gen as I should be.

Trending

-

Anyone planning to relocate to Somalia or is everyone too comfortable in the western world?

- Started by Kamaaludeen Al Reewin

- Replies: 54

-

-

Im acc tired of people telling any somali they see they look like "insert beta squad member"

- Started by kamek

- Replies: 97