Old school liberalism is quite rightwing. It doesn't help out the poor and is extremely market oriented.

Nowadays, especially in American English, liberalism usually means something close to Social Democracy and not old school (1800s) liberalism.

The left-right dichotomy really is a poor model of explaining politics.

Let me introduce the concepts of the principled and unprincipled exceptions. These account for the variations in the stances of social democracy, classic liberalism, neoliberalism and what not. The unprincipled exception is a non-liberal value or assertion,

not explicitly identified as non-liberal, which individuals use in order to avoid certain aspects of liberalism. The principled exception is its inversion: a non-liberal value, explicitly identified as non-liberal, which individuals use to avoid certain aspects of liberalism. The movement between principled exception to unprincipled exception helps explain much of the progression of liberalism.

Remember: liberalism's heart is that liberty (freedom) is the ultimate good.

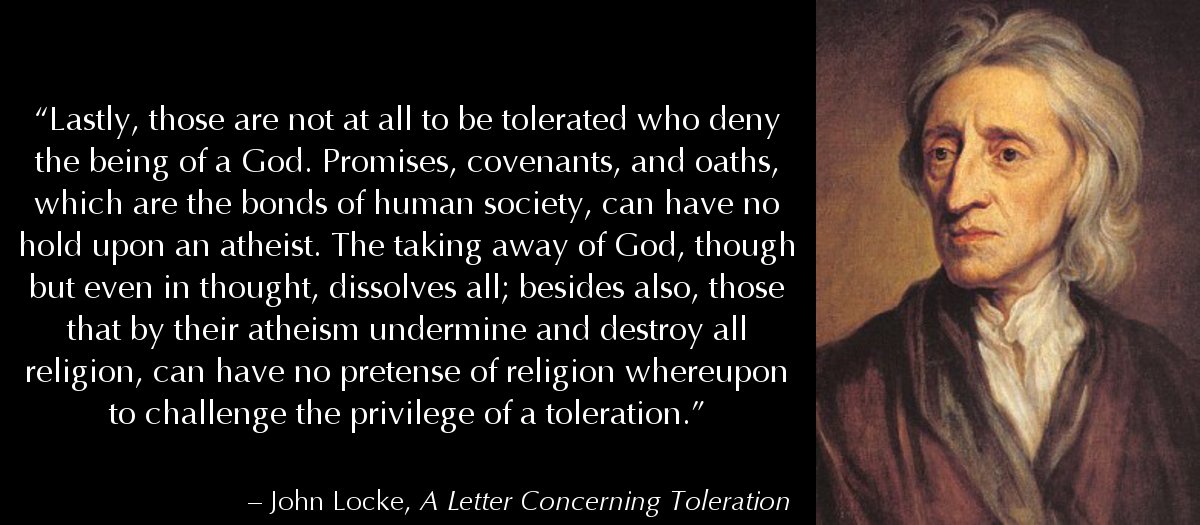

Liberalism emerged in the UK in the 17th century which was marked by the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, the Protectorate of Cromwell, the Restoration and the Glorious Revolution. Back then, virtually everyone were Christian. This was to the point that John Locke, major liberal philosopher, advocated for freedom of religion (meaning freedom to be Catholic, Anglican or nonconforming Christian). What was his view on atheism, I wonder?

This is a principled exception. Over time, this stance becomes an unprincipled exception. Generations are brought up being taught that freedom is the ultimate good and also being taught contradictory things like Christianity. This causes cognitive dissonance so they switch to unprincipled exceptions: atheists are bad people, untrustworthy, traitors and so forth. Here is the point: no matter whether their excuses are true or not, they have ceased to argue in the name of their non-liberal beliefs, appealing to common sense or emotion or something like that. This is an unprincipled exception: they have become unwilling to challenge liberalism directly. Their non-liberal beliefs are incompletely passed down to future generations who then largely disregard it. Without the non-liberal foundations, the unprincipled exception is weak and is easily wiped away by the forces of liberalism.

This is the internal dialectic of liberalism: you can trace it to so many different issues. The key is: once an exception becomes unprincipled, liberalism has won (no matter how long it takes).

Social democracy, the extension of democratic control to the economic sphere, was formed by the efforts of many revisionist Marxists, Christian Socialists, Fabian Socialists and more. These people mounted a challenge to the predominant economic liberalism using principled exceptions that drew on things like historical materialism, Christian duty and agape and utopian socialism. Over a few decades, these principled exceptions degenerated to unprincipled exceptions like the poor need help. These sentiments, however nice, have weak foundations. Then, in the 90s, social democratic parties began to reintroduce marketisation, calling card of economic liberalism.

What does this internal dialectic of liberalism mean? Any issue on which a defence cannot proudly be mounted using non-liberal justifications will fall to liberalism. Homosexuality, marketisation of society, dissolution of family ties, loss of tradition, sexual liberation, you name it. This helps explain the sudden turn around on transgenderism over the last 10 years. See if this theory applies in real life: such theories are as truthful as they are explanatorily powerful.

Although most Russian Jews are not mixed with Asians (they mostly look like European/North American Jews).

Although most Russian Jews are not mixed with Asians (they mostly look like European/North American Jews).