The composite bow, which created and destroyed empires, was the most effective of medieval weapons before the advent of the gun.

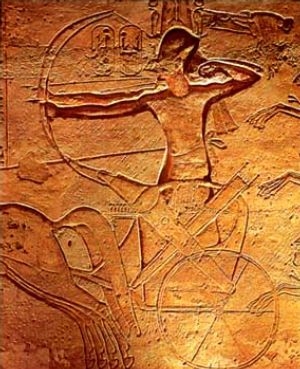

The origins of this remarkable innovation have long been debated, with visual imagery providing the only proof. Recent research places its appearance at Mari, a mid-third millennium 2500 bc Early Dynastic city in what is now Syria. Somewhat later, a dramatic representation of the composite bow was carved on one of the most famous steles of the ancient world. It depicts the Akkadian king Naramsin, grandson of Sargon I, firmly grasping the bow in his right hand as he grinds his enemies into the dust, during the 2250 bc. The stele illustrates the world’s first instance of a living ruler proclaiming himself divine: Naramsin wears the horned helmet of a deified hero. Significantly, this new divinity’s weapon of choice was the composite bow.

Bows and arrows had of course been in use since prehistoric times, going back at least 40,000 years. Spanish caves have 10,000-year-old rock paintings that show pitched battles between combatants armed with bows. These simple or “self” bows (from the meaning of the word “being uniform throughout”) were made from a single stave of wood, strung with a string from which the arrow was propelled. Although uncomplicated, they were effective weapons, allowing men to fire at an animal or an enemy from a relatively safe distance.

At some point in the past, after decades or, more likely, centuries of experimentation, driven by the need to improve accuracy, power, and range to subdue their opponents or bring down game, clever and determined artisans developed the composite bow. Theirs was an immense technological advancement that would change the face of warfare in the East.

A Feat of Engineering

The name itself belies its construction. The basic structure consisted of a grip, two arms, and two tips, all of plain or laminated wood. These were bound together using a glue made by boiling down fish bones and cattle tendons. The slender strips of wood were then curved by steaming and slivers of animal horn were glued on the inner side, or “belly” of the bow. Then the bow was bent into a circle and animal sinew was glued on to the outer side, or the “back.” The horn section faced the archer and compressed when the bow was drawn; the animal tendon on the outside provided tension. The wooden part of the bow ended up being little more than a core, but of no less equal importance to the entire structure because it absorbed stress. As the bowman drew the string to shoot, all the various components of this engineering wonder smoothly came into play: the horn resisted compression, the sinew flexed, and the wood took the stress as the bow was made taut when drawn and then snapped back into shape upon release of the arrow.

The composite bow’s power and performance came not only from its unique design, but also from the correct application of the best materials available. Only special types of carefully selected sinew, wood, and horn were suitable for making composite bows. Illustrated in a document from Ugarit, a Bronze Age city, the epic hero Aqhat swears to provide the goddess Anat with the required materials:

“Let me vow ‘tqbm from Lebanon

Let me vow tendons from wild bulls

Let me vow horns from wild goats

Sinews from the locks of bulls.”

Another feat of engineering skill—and again the culmination of many prototypes and years of development—was to bend the tips of the bow to which the string was attached in the opposite direction of the draw, giving this highest development of the composite bow a distinctive “recurved” shape, dramatically increasing velocity and impact.

The composite bow was then left to cure for a year or more in storage rooms where humidity and temperature where highly regulated, allowing its various elements to meld into each other. If any of these procedures were not precisely followed, the bow would buckle or rip apart in the archer’s hands while being drawn. At the end of the curing period, the bows were tested and adjusted.

The manufacture of these weapons was time-consuming, labor-intensive, and expensive, requiring highly specialized training in the bowyers. “A great deal of art,” writes one researcher, “was involved in their preparation and application, much of it characterized by a mystical, semi-religious approach.” The bowyers passed their art and knowledge down to succeeding generations. The finished bow was a thing of great beauty, worth, and elegance, and each had its own “personality.” They were usually painted with intricate designs, stored in specially made protective cases, and only entrusted to the best archers.

The origins of this remarkable innovation have long been debated, with visual imagery providing the only proof. Recent research places its appearance at Mari, a mid-third millennium 2500 bc Early Dynastic city in what is now Syria. Somewhat later, a dramatic representation of the composite bow was carved on one of the most famous steles of the ancient world. It depicts the Akkadian king Naramsin, grandson of Sargon I, firmly grasping the bow in his right hand as he grinds his enemies into the dust, during the 2250 bc. The stele illustrates the world’s first instance of a living ruler proclaiming himself divine: Naramsin wears the horned helmet of a deified hero. Significantly, this new divinity’s weapon of choice was the composite bow.

Bows and arrows had of course been in use since prehistoric times, going back at least 40,000 years. Spanish caves have 10,000-year-old rock paintings that show pitched battles between combatants armed with bows. These simple or “self” bows (from the meaning of the word “being uniform throughout”) were made from a single stave of wood, strung with a string from which the arrow was propelled. Although uncomplicated, they were effective weapons, allowing men to fire at an animal or an enemy from a relatively safe distance.

At some point in the past, after decades or, more likely, centuries of experimentation, driven by the need to improve accuracy, power, and range to subdue their opponents or bring down game, clever and determined artisans developed the composite bow. Theirs was an immense technological advancement that would change the face of warfare in the East.

A Feat of Engineering

The name itself belies its construction. The basic structure consisted of a grip, two arms, and two tips, all of plain or laminated wood. These were bound together using a glue made by boiling down fish bones and cattle tendons. The slender strips of wood were then curved by steaming and slivers of animal horn were glued on the inner side, or “belly” of the bow. Then the bow was bent into a circle and animal sinew was glued on to the outer side, or the “back.” The horn section faced the archer and compressed when the bow was drawn; the animal tendon on the outside provided tension. The wooden part of the bow ended up being little more than a core, but of no less equal importance to the entire structure because it absorbed stress. As the bowman drew the string to shoot, all the various components of this engineering wonder smoothly came into play: the horn resisted compression, the sinew flexed, and the wood took the stress as the bow was made taut when drawn and then snapped back into shape upon release of the arrow.

The composite bow’s power and performance came not only from its unique design, but also from the correct application of the best materials available. Only special types of carefully selected sinew, wood, and horn were suitable for making composite bows. Illustrated in a document from Ugarit, a Bronze Age city, the epic hero Aqhat swears to provide the goddess Anat with the required materials:

“Let me vow ‘tqbm from Lebanon

Let me vow tendons from wild bulls

Let me vow horns from wild goats

Sinews from the locks of bulls.”

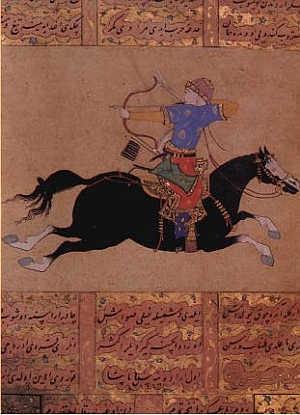

Another feat of engineering skill—and again the culmination of many prototypes and years of development—was to bend the tips of the bow to which the string was attached in the opposite direction of the draw, giving this highest development of the composite bow a distinctive “recurved” shape, dramatically increasing velocity and impact.

The composite bow was then left to cure for a year or more in storage rooms where humidity and temperature where highly regulated, allowing its various elements to meld into each other. If any of these procedures were not precisely followed, the bow would buckle or rip apart in the archer’s hands while being drawn. At the end of the curing period, the bows were tested and adjusted.

The manufacture of these weapons was time-consuming, labor-intensive, and expensive, requiring highly specialized training in the bowyers. “A great deal of art,” writes one researcher, “was involved in their preparation and application, much of it characterized by a mystical, semi-religious approach.” The bowyers passed their art and knowledge down to succeeding generations. The finished bow was a thing of great beauty, worth, and elegance, and each had its own “personality.” They were usually painted with intricate designs, stored in specially made protective cases, and only entrusted to the best archers.