This is a very important thread because many people falsely believe the myth, Somalia was self-sufficient during the times of relatively stability, pre civil war (1960-1991). I will post several reliable sources, mainly academical journals, to prove that the opposite case is true.

#Fact 1: The civilian governments between 1960-1969 received more aid money than any other African country per capita. The ruling party in this Era the Somali Youth League or in short SYL, based the major part of it's financial policy on aid money. Read the below sources.

1) "SOMALIA is one of the poorest countries of the world, with an estimated income per capita of about $50.1 Yet she is one of the largest recipients of foreign aid: during I964-9 she received an annual average of about $15 per head of her 3 million population.2 This rate of aid is more than three times the figure of $4.5 per capita, which represents the average annual aid to other developing countries during I964-7.3 The large inflow of foreign aid to Somalia reflects both a great variety of forms of economic assistance and an uncommon diversity of donors. Most significantly, about 85 per cent of her total development expendi- ture up to the end of 1969 has been externally financed. This is a rare case of dependence on foreign financing among the less developed countries, where typically foreign resources account for only about I0 per cent of total investment expenditure. Consequently, Somalia presents a unique opportunity for a case study of the effectiveness of foreign aid to a country at an early stage of development. To anticipate the overall conclusions of this article, her experience suggests that aid is far from being an unqualified bonus"

Effectiveness of Foreign Aid-The Case of Somalia

Author(s): Ozay Mehmet

Source: The Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol. 9, No. 1 (May, 1971), pp. 31-47

Published by: Cambridge University Press

2) "The most significant change in the first nine years of independence was in the growth of public employment. In order to pay for the enormous growth in recurrent expenditure to employ so many people, Somali leaders engaged in an inventive strategy of playing off the two superpowers against each other. Refusing either to be 'capitalist' or 'communist' but appearing to be interested in both, Somali leaders procured more international aid per capita than any other country in Africa. In the decade of the 1960s, Somalia received US$90 per capita in foreign economic assistance, about twice the average for sub-Saharan Africa. This helped to pay for increasing numbers of bureaucrats and parliamentarians, who lived ostentatious and opulent lives in Mogadishu, and for a five fold increase in the size of the Somali army. To be sure, much of the foreign aid did go into infrastructural investment and other worthy projects. In this period, the state constructed roads, factories to produce milk, textiles, tinned meat and fish. Also many schools, a national theatre, and a national airline. But most Somalis - and the aid officials who were supposedly overseeing these investments - felt frustrated. Factory production barely got off the ground and was beset with endless delays. Medicine donated by the World Health Organisation found its way into private pharmacies; foreign exchange for development projects was expended for vehicles that became private taxis owned by the families of parliamentarians; and the custom's duties were privately appropriated. An aura of corruption - what the Somalis call musuq maasuq - pervaded all of Somali economic life. This subverted the ability of the state to lead Somali out of the economic doldrums."

Somalia and the World Economy

Author(s): David D. Laitin and Said S. Samatar

Source: Review of African Political Economy, No. 30, Conflict in the Horn of Africa (Sep., 1984), pp. 58-72 Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd.

#Fact 2: The regime of Mohammed Siyad Barre did not make Somalia self-sufficient either, rather the dependency on aid money increased rapidly during the 21 years rule of the dictator. As follows, you will see my sources.

1) "Here it ought to be mentioned that although Somalia no longer relies on western capitalist aid as it had done so heavily in the I96os, the present aid, from the Soviet Union, is facing the same difficulties. The egalitarian and proud Somali workers seem reluctant to implement certain projects, as if to 'get back' at certain dogmatic and arrogant Russians. While the Somali Government becomes more and more in debt to the Soviet Union, results from the economic aid - in particular the meat factory and the fishing industry - are far below expectations."

The Political Economy of Military Rule in Somalia

Author(s): David D. Laitin

Source: The Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol. 14, No. 3 (Sep., 1976), pp. 449-468

Published by: Cambridge University Press

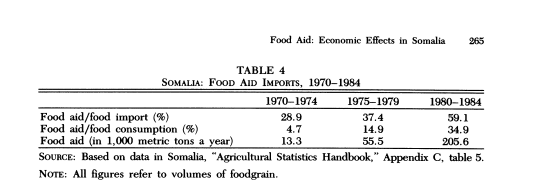

2) "To meet its domestic demand for food, Somalia became increasingly dependent on food aid. This fact is clear from table 4, which shows that within a decade the inflow of food aid grew by more than 15-fold, or at the striking rate of 31 percent a year, thus outpacing the 8.2 per- cent annual growth of food consumption by 3.8 times. As a consequence, the share of food aid in consumption rose rapidly from virtually nil in the early 1970s to about one-third in the early 1980s.

The growing dependence on food aid has sometimes been justified on the grounds that development efforts in the early stages result in per capita income growth, which together with an initially high population growth rate and a relatively high income elasticity of demand for food in the low-income developing countries leads to a growth in food demand at a faster rate than can be met by increases in domestic production. This brings about an increased dependence on food imports in general and on food aid in particular when foreign-exchange scarcity severely constrains commercial imports.2' For the specific case of Somalia, how- ever, it is highly doubtful that this argument holds. The reason is that, although a high income elasticity of food demand in Somalia is quite plausible (and is in fact confirmed by Farzin's estimating it to be around 1.4 and statistically highly significant), and although Somalia's population grew at the high average rate of about 3.5 percent a year,22 its real per capita income not only did not grow, but in fact declined over this period at the average rate of -0.3 percent a year."

Food Aid: Positive or Negative Economic Effects in Somalia?

Author(s): Y. Hossein Farzin

Source: The Journal of Developing Areas, Vol. 25, No. 2 (Jan., 1991), pp. 261-282

Published by: College of Business, Tennessee State University

3) "By the early 1980s, Somalia had accumulated over $600 million of debt -four times the revenues from exports. Put another way, in 1983, the country's service payments on existing debts were well over 25 percent of expected revenues from exports. Interview with Xussein Celaabay, Director General, State Planning Commission, Moqdishu, 12 December 1982. Moreover, the economy's dependence on foreign aid is put around 40 percent ($400 million) of the Gross Natinal Product. Virginia Luling, `Somalia," Africa Review, 1985, 9th ed. (Essex: World of Information, 1985), pp. 290-92"

Underdevelopment in Somalia: Dictatorship without Hegemony

Author(s): Ahmed I. Samatar

Source: Africa Today, Vol. 32, No. 3, Somalia: Crises of State and Society (3rd Qtr., 1985), pp. 23-40

Published by: Indiana University Press

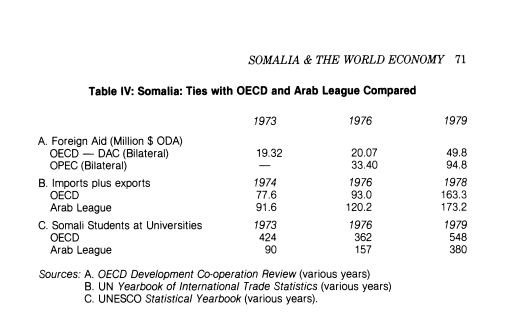

4)

Somalia and the World Economy

Author(s): David D. Laitin and Said S. Samatar

Source: Review of African Political Economy, No. 30, Conflict in the Horn of Africa (Sep., 1984), pp. 58-72 Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd.

5) "The entire country has suffered severe setbacks caused by economic inertia, intense inflationary pressures induced by the war, and the cost of a large and unproductive bureaucracy. The disorder engendered by this process has led to the misappropriation of the nation's wealth by officials in ways that were previously unimaginable. It is usually in the upper echelons of the public service that the bulk of the sacking of the commons takes place, while most bureaucrats, whose salaries have been virtually swallowed by inflation, garner whatever they can by exploiting their offices. This is the social basis for corruption, bearing in mind that a mid-level functionary only earns about S.Shs.i,ooo a month, just enough to purchase, for example, 7 kilos of meat. In addition, the shift (in the mid-1970s) from eastern to western sources of aid, with its emphasis on private rather than public programmes, facilitates the vigour with which plundering is taking place. State agencies, ministries, and parastatals, because they are strategic recipients of foreign aid or 'rent', are zealously guarded by those who command state power,1 and there is enough evidence to suggest that important developmental agencies and departments have been hijacked by members of the ruling clique. Moreover, the vast amounts of foreign assistance which the military regime continues to receive2 - Table i shows that in Africa only Mauritania and Botswana are higher recipients of aid on a per capita basis - and the rentier nature of the leadership, deepens the wedge between the state and the rural producers, currently responsible for nearly go per cent of the country's foreign exchange."

The Material Roots of the Suspended African State: Arguments from Somalia

Author(s): Abdi Samatar and A. I. Samatar

Source: The Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol. 25, No. 4 (Dec., 1987), pp. 669-690

Published by: Cambridge University Press

#Fact 1: The civilian governments between 1960-1969 received more aid money than any other African country per capita. The ruling party in this Era the Somali Youth League or in short SYL, based the major part of it's financial policy on aid money. Read the below sources.

1) "SOMALIA is one of the poorest countries of the world, with an estimated income per capita of about $50.1 Yet she is one of the largest recipients of foreign aid: during I964-9 she received an annual average of about $15 per head of her 3 million population.2 This rate of aid is more than three times the figure of $4.5 per capita, which represents the average annual aid to other developing countries during I964-7.3 The large inflow of foreign aid to Somalia reflects both a great variety of forms of economic assistance and an uncommon diversity of donors. Most significantly, about 85 per cent of her total development expendi- ture up to the end of 1969 has been externally financed. This is a rare case of dependence on foreign financing among the less developed countries, where typically foreign resources account for only about I0 per cent of total investment expenditure. Consequently, Somalia presents a unique opportunity for a case study of the effectiveness of foreign aid to a country at an early stage of development. To anticipate the overall conclusions of this article, her experience suggests that aid is far from being an unqualified bonus"

Effectiveness of Foreign Aid-The Case of Somalia

Author(s): Ozay Mehmet

Source: The Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol. 9, No. 1 (May, 1971), pp. 31-47

Published by: Cambridge University Press

2) "The most significant change in the first nine years of independence was in the growth of public employment. In order to pay for the enormous growth in recurrent expenditure to employ so many people, Somali leaders engaged in an inventive strategy of playing off the two superpowers against each other. Refusing either to be 'capitalist' or 'communist' but appearing to be interested in both, Somali leaders procured more international aid per capita than any other country in Africa. In the decade of the 1960s, Somalia received US$90 per capita in foreign economic assistance, about twice the average for sub-Saharan Africa. This helped to pay for increasing numbers of bureaucrats and parliamentarians, who lived ostentatious and opulent lives in Mogadishu, and for a five fold increase in the size of the Somali army. To be sure, much of the foreign aid did go into infrastructural investment and other worthy projects. In this period, the state constructed roads, factories to produce milk, textiles, tinned meat and fish. Also many schools, a national theatre, and a national airline. But most Somalis - and the aid officials who were supposedly overseeing these investments - felt frustrated. Factory production barely got off the ground and was beset with endless delays. Medicine donated by the World Health Organisation found its way into private pharmacies; foreign exchange for development projects was expended for vehicles that became private taxis owned by the families of parliamentarians; and the custom's duties were privately appropriated. An aura of corruption - what the Somalis call musuq maasuq - pervaded all of Somali economic life. This subverted the ability of the state to lead Somali out of the economic doldrums."

Somalia and the World Economy

Author(s): David D. Laitin and Said S. Samatar

Source: Review of African Political Economy, No. 30, Conflict in the Horn of Africa (Sep., 1984), pp. 58-72 Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd.

#Fact 2: The regime of Mohammed Siyad Barre did not make Somalia self-sufficient either, rather the dependency on aid money increased rapidly during the 21 years rule of the dictator. As follows, you will see my sources.

1) "Here it ought to be mentioned that although Somalia no longer relies on western capitalist aid as it had done so heavily in the I96os, the present aid, from the Soviet Union, is facing the same difficulties. The egalitarian and proud Somali workers seem reluctant to implement certain projects, as if to 'get back' at certain dogmatic and arrogant Russians. While the Somali Government becomes more and more in debt to the Soviet Union, results from the economic aid - in particular the meat factory and the fishing industry - are far below expectations."

The Political Economy of Military Rule in Somalia

Author(s): David D. Laitin

Source: The Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol. 14, No. 3 (Sep., 1976), pp. 449-468

Published by: Cambridge University Press

2) "To meet its domestic demand for food, Somalia became increasingly dependent on food aid. This fact is clear from table 4, which shows that within a decade the inflow of food aid grew by more than 15-fold, or at the striking rate of 31 percent a year, thus outpacing the 8.2 per- cent annual growth of food consumption by 3.8 times. As a consequence, the share of food aid in consumption rose rapidly from virtually nil in the early 1970s to about one-third in the early 1980s.

The growing dependence on food aid has sometimes been justified on the grounds that development efforts in the early stages result in per capita income growth, which together with an initially high population growth rate and a relatively high income elasticity of demand for food in the low-income developing countries leads to a growth in food demand at a faster rate than can be met by increases in domestic production. This brings about an increased dependence on food imports in general and on food aid in particular when foreign-exchange scarcity severely constrains commercial imports.2' For the specific case of Somalia, how- ever, it is highly doubtful that this argument holds. The reason is that, although a high income elasticity of food demand in Somalia is quite plausible (and is in fact confirmed by Farzin's estimating it to be around 1.4 and statistically highly significant), and although Somalia's population grew at the high average rate of about 3.5 percent a year,22 its real per capita income not only did not grow, but in fact declined over this period at the average rate of -0.3 percent a year."

Food Aid: Positive or Negative Economic Effects in Somalia?

Author(s): Y. Hossein Farzin

Source: The Journal of Developing Areas, Vol. 25, No. 2 (Jan., 1991), pp. 261-282

Published by: College of Business, Tennessee State University

3) "By the early 1980s, Somalia had accumulated over $600 million of debt -four times the revenues from exports. Put another way, in 1983, the country's service payments on existing debts were well over 25 percent of expected revenues from exports. Interview with Xussein Celaabay, Director General, State Planning Commission, Moqdishu, 12 December 1982. Moreover, the economy's dependence on foreign aid is put around 40 percent ($400 million) of the Gross Natinal Product. Virginia Luling, `Somalia," Africa Review, 1985, 9th ed. (Essex: World of Information, 1985), pp. 290-92"

Underdevelopment in Somalia: Dictatorship without Hegemony

Author(s): Ahmed I. Samatar

Source: Africa Today, Vol. 32, No. 3, Somalia: Crises of State and Society (3rd Qtr., 1985), pp. 23-40

Published by: Indiana University Press

4)

Somalia and the World Economy

Author(s): David D. Laitin and Said S. Samatar

Source: Review of African Political Economy, No. 30, Conflict in the Horn of Africa (Sep., 1984), pp. 58-72 Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd.

5) "The entire country has suffered severe setbacks caused by economic inertia, intense inflationary pressures induced by the war, and the cost of a large and unproductive bureaucracy. The disorder engendered by this process has led to the misappropriation of the nation's wealth by officials in ways that were previously unimaginable. It is usually in the upper echelons of the public service that the bulk of the sacking of the commons takes place, while most bureaucrats, whose salaries have been virtually swallowed by inflation, garner whatever they can by exploiting their offices. This is the social basis for corruption, bearing in mind that a mid-level functionary only earns about S.Shs.i,ooo a month, just enough to purchase, for example, 7 kilos of meat. In addition, the shift (in the mid-1970s) from eastern to western sources of aid, with its emphasis on private rather than public programmes, facilitates the vigour with which plundering is taking place. State agencies, ministries, and parastatals, because they are strategic recipients of foreign aid or 'rent', are zealously guarded by those who command state power,1 and there is enough evidence to suggest that important developmental agencies and departments have been hijacked by members of the ruling clique. Moreover, the vast amounts of foreign assistance which the military regime continues to receive2 - Table i shows that in Africa only Mauritania and Botswana are higher recipients of aid on a per capita basis - and the rentier nature of the leadership, deepens the wedge between the state and the rural producers, currently responsible for nearly go per cent of the country's foreign exchange."

The Material Roots of the Suspended African State: Arguments from Somalia

Author(s): Abdi Samatar and A. I. Samatar

Source: The Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol. 25, No. 4 (Dec., 1987), pp. 669-690

Published by: Cambridge University Press

Last edited: