Very little effort has been put on the preservation of Somali cultural heritage and archaeological remains in the last century or so. The little efforts made to preserve Somali cultural heritage in the last five decades have ultimately failed. This is evident from the ways that Somali cultural heritage and archaeological research has been pursued in colonial times and postcolonial times, prior to the commencement of the civil war. It is partly due to a lack of recognition of the significance of an appropriate dialogue and communication between various groups who have an interest in the preservation of this heritage. This failure is also due to a neglect of Somali cultural heritage that has continued during the on-going civil war. In the last 18 years warlords have commissioned illicit diggings to finance the war, while the poverty also has led to others taking up looting and selling of artefacts. The result is one of the worst records of loss of archaeological remains in the Horn of Africa. Consequently, Somali people are losing their only source of (pre-)history.

The UN member nation-state of Somalia consists today of a war-torn society made of three new regions, these are Somaliland, Puntland and south-central Somalia. Somaliland is a break-away region with its own government which seeks an international recognition as an independent nation-state. Puntland is a semiautonomous region.

Puntland and south-central Somalia are still facing instabilities due to ongoing war and piracy. Furthermore, severe poverty and prolonged droughts threaten all Somali regions.

The archaeology of Somalia, Puntland and Somaliland is disappearing systematically. Some people are destroying the archaeological heritage by looting and clandestine excavations. Archaeology has become a source to feed upon during these difficult conditions. However, without the demand for antiquities by privileged outsiders such illicit activities would not have escalated to the degrees they have.

Since severe poverty mostly triggers these activities the solution to the problem needs to be multiple. The potentials of cultural heritage resources must be highlighted to the current looters and it must be made explicit how future possibilities for education, job opportunities and tourism can benefit them in the long term.

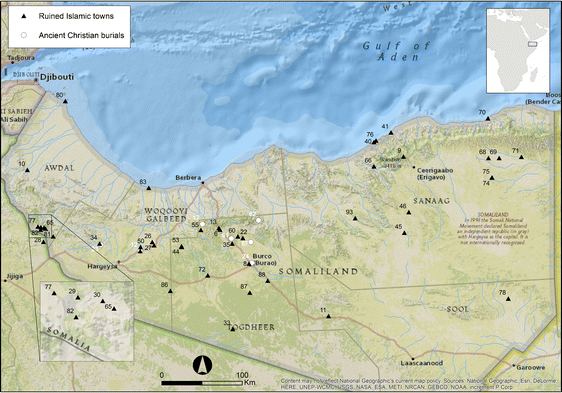

In Post-conflict Somaliland, which provides a peaceful society within which to promote heritage management, the Department of Antiquities has put measures in place to protect cultural heritage resources. For example, many archaeological sites are put under the supervision of prominent locals. However, these contain just a fraction of the known archaeological sites and many more sites need supervision. Furthermore, these measures are the bare minimum. Documentation, recording and conservation are still to be implemented.

Coupled with lack of knowledge about the significance of the archaeological heritage, the problems will remain. Many people show great interest in cultural resource management and there is a need for trained archaeologists and heritage workers to work with them and study the history of the region together with the locals. The locals usually hold great knowledge about their areas.

Mire's work with the Department of Antiquities attempts to consolidate the archaeology for control of a governmental body. Hence the setting up of the Department of Antiquities was a first step. This department is the authority that manages heritage on state level, protects it and communicates its significance to the people of the country. However, the challenges remain in terms of the lack of trained locals for heritage management and preservation, as well as the lack of museums to place collections for protection, research or display.

Somaliland is rich on cultural heritage and archaeological remains; therefore the government needs to build future strategy for its archaeology. Although the infrastructure for tourism is poor, there are enough sites today, however, that are near Hargeysa, the capital of Somaliland. These include rock art sites that provide a ready resource for tourism. These would not require substantial facilities only if the much needed site protection and conservation are implemented. The benefit can result into economic and educational tourism of these sites which are easy to access, the Somaliland government and its people will benefit from such development. Therefore, the Department of Antiquities is currently developing with the assistance of Sada Mire the tourism strategy and management of sites such as Laas Geel and Dhagah Kure, near Hargeysa.

The UN member nation-state of Somalia consists today of a war-torn society made of three new regions, these are Somaliland, Puntland and south-central Somalia. Somaliland is a break-away region with its own government which seeks an international recognition as an independent nation-state. Puntland is a semiautonomous region.

Puntland and south-central Somalia are still facing instabilities due to ongoing war and piracy. Furthermore, severe poverty and prolonged droughts threaten all Somali regions.

The archaeology of Somalia, Puntland and Somaliland is disappearing systematically. Some people are destroying the archaeological heritage by looting and clandestine excavations. Archaeology has become a source to feed upon during these difficult conditions. However, without the demand for antiquities by privileged outsiders such illicit activities would not have escalated to the degrees they have.

Since severe poverty mostly triggers these activities the solution to the problem needs to be multiple. The potentials of cultural heritage resources must be highlighted to the current looters and it must be made explicit how future possibilities for education, job opportunities and tourism can benefit them in the long term.

In Post-conflict Somaliland, which provides a peaceful society within which to promote heritage management, the Department of Antiquities has put measures in place to protect cultural heritage resources. For example, many archaeological sites are put under the supervision of prominent locals. However, these contain just a fraction of the known archaeological sites and many more sites need supervision. Furthermore, these measures are the bare minimum. Documentation, recording and conservation are still to be implemented.

Coupled with lack of knowledge about the significance of the archaeological heritage, the problems will remain. Many people show great interest in cultural resource management and there is a need for trained archaeologists and heritage workers to work with them and study the history of the region together with the locals. The locals usually hold great knowledge about their areas.

Mire's work with the Department of Antiquities attempts to consolidate the archaeology for control of a governmental body. Hence the setting up of the Department of Antiquities was a first step. This department is the authority that manages heritage on state level, protects it and communicates its significance to the people of the country. However, the challenges remain in terms of the lack of trained locals for heritage management and preservation, as well as the lack of museums to place collections for protection, research or display.

Somaliland is rich on cultural heritage and archaeological remains; therefore the government needs to build future strategy for its archaeology. Although the infrastructure for tourism is poor, there are enough sites today, however, that are near Hargeysa, the capital of Somaliland. These include rock art sites that provide a ready resource for tourism. These would not require substantial facilities only if the much needed site protection and conservation are implemented. The benefit can result into economic and educational tourism of these sites which are easy to access, the Somaliland government and its people will benefit from such development. Therefore, the Department of Antiquities is currently developing with the assistance of Sada Mire the tourism strategy and management of sites such as Laas Geel and Dhagah Kure, near Hargeysa.

human garbage smh all of our artifacts need to be kept in a highly secured museum

human garbage smh all of our artifacts need to be kept in a highly secured museum