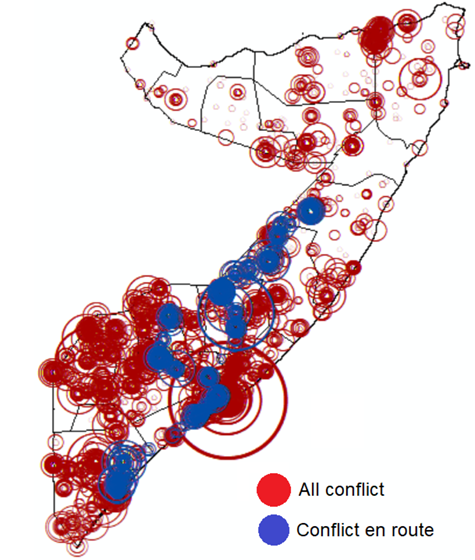

Fairly surprising that the price of maize in Gaalkacyo is affected to this degree by conflict in southern Somalia.

Very important point made here about the fact that damage to transportation corridors is not as limited as many seem to believe:

Source: Spatial Spillovers of Conflict in Somalia

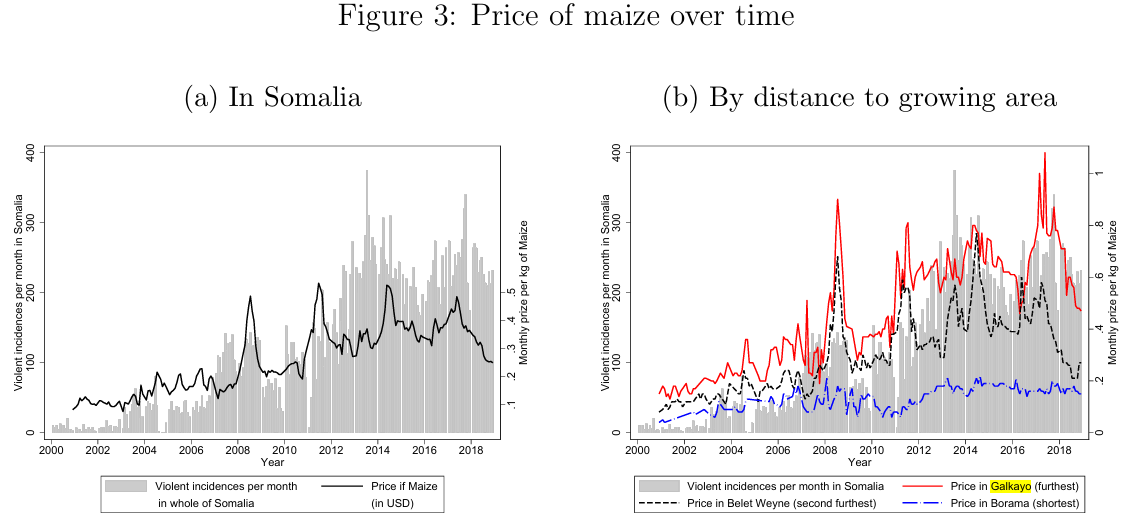

Figure 3b shows the price in three selected markets, each located at a different distance to growing areas. Before the al-Shabaab insurgency in the early-2000s, prices are similar and show parallel trends. After the insurgency, price increases are strongest in Galkayo (transportation route of 900 kilometers, with many attacks en route), followed by Belet Weyne (transportation route of 400 kilometers, with fewer attacks en route) with no changes in Borama (located next to a growing area, therefore no attacks along the road). These descriptive results provide preliminary evidence of a positive association between market prices and attacks along the transportation routes serving the markets.

This study is the first to document that food prices play an important role in enabling conflict to affect important human capital outcomes (nutrition, health and education) of in dividuals hundreds of kilometres away. Our findings have wide-ranging policy implications. Spatial spillovers of conflict induce important additional welfare costs, implying that the adverse effects of conflict on human capital are larger than commonly assumed. Back of the envelope calculations suggest that spatial spillovers add around 30% to the welfare cost of local conflict, further strengthening the case for humanitarian interventions in response to violent conflict, possibly through nutritional subsidies. Our findings also have important implications for the regional targeting of policies such as humanitarian aid, protection efforts, or asylum status eligibility, which would potentially need to be broadened. In Somalia, for instance, the World Health Organisation (WHO) provides emergency medical supplies to areas affected by conflict.7 Our findings that individuals far away from conflict are impacted make the case to extend such aid to other areas of the country.

Very important point made here about the fact that damage to transportation corridors is not as limited as many seem to believe:

Humanitarian interventions or refugee policies most commonly focus on those locations where the conflict occurs. The Word Food Programme (WFP, 2021), for instance, provides nutritional assistance to areas around Mogadishu, in the Southwest of Somalia where most of the fighting is concentrated. Similarly, when evaluating asylum eligibility, the United Nations High Commission for Refugees report (UNHCR, 2010) highlights the Southwest of Somalia in particular as the area where individuals are at risk of serious harm. By contrast, our results provide evidence that individuals can be affected by conflict even if it occurs far away. For instance, the city of Galkayo (located 700km from Mogadishu, corresponding to a 14 hour drive) is part of the northeastern region of Puntland and as such not covered by either the WFP or UNHCR policies mentioned above. Our analysis, however, shows that conflict occurring in the Southwest increases food prices, decreases food security and erodes human capital in Galkayo thus suggesting that policies regarding conflict should broaden their scope.

Source: Spatial Spillovers of Conflict in Somalia