@Grant East African dromedaries are the most divergent lineage of camel there is. It has been relatively isolated for 7,700 years from other camel populations. If I had to hazard a guess it would be that the introduction of the camel in East Africa precedes its introduction in Northern Arabia. The camel population of East Africa seems to have been directly imported from an already divergent population in Southern Arabia while still semi-domesticated. The reason I say this is that camel domestication only began 5,000 years ago, the East African camel was already separate from other population even in the wild. This may even support the claim that domestication occurred in East Africa

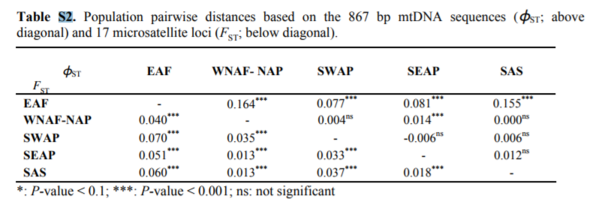

(Fst) in the graph below is data for nuclear DNA and (Φst) is mitochondrial DNA. You can see that the East African (EAF) cluster is distant to all the other populations.

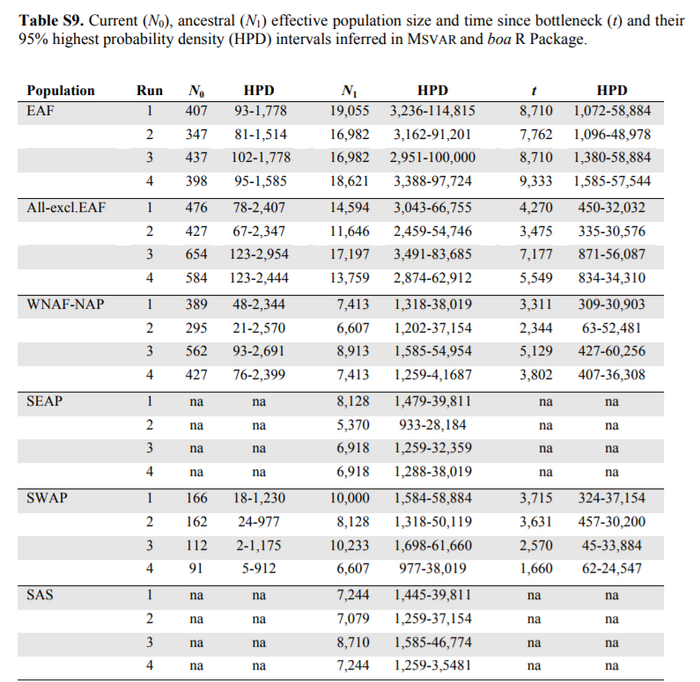

They then go on to estimate the time since divergence and it is significantly before domestication. They seem to discount the possibility of there having been a population of camel that was native to East Africa considering the existence of a land bridge between East Africa and Southern Arabia.

http://www.pnas.org/content/113/24/6707.full

Your link:

"Introduction of Arabian dromedaries into Africa.

The absence of genetic structure between WNAF and NAP (ϕST = 0.006;

P < 0.001;

FST = −0.002;

P > 0.05) points to an extensive exchange of dromedaries introduced into northeastern Africa from the Arabian Peninsula via the Sinai (

SI Appendix, Fig. S4), possibly starting in the early first millennium BCE and intensifying in the Ptolemaic period (

1,

17). From here, dromedaries spread across northern Africa, but their adoption into local economies may have been slow, considering that the first unequivocal evidence for their presence in northwestern Africa comes from archaeological layers dating to the fourth to the seventh century CE (Late Antiquity/Early Middle Ages) (

SI Appendix). Although WNAF-NAP showed close cross-continental affinities with Southern Arabian and Asian dromedaries, the two African populations were genetically the most distant (EAF/WNAF-NAP ϕST = 0.164;

FST = 0.040;

P < 0.001), in contrast with their geographical proximity. The lowest pairwise genetic distances for Eastern African dromedaries were actually measured with the SAP populations (

SI Appendix, Table S2), suggesting a few possible routes for domestic dromedaries to be introduced to Eastern Africa. These involve the transfer from the Arabian Peninsula by boat either directly across the Gulf of Aden or further north across the Red Sea to Egypt and then traveling south along the western coast of the Red Sea to northwestern Sudan, Eritrea, and Ethiopia (

SI Appendix, Fig. S4). A seaborne introduction appears likely, because there is increasing evidence that the southern Arabian Peninsula played an important role in domestication [e.g., African wild ass (

29)] and in the transfer of crops and livestock [e.g., zebu cattle, fat-tailed sheep (

30,

31)] between South Asia and the African continent. Additional evidence for a separate introduction might come from socio-ethological observations; today’s Eastern African dromedaries are used largely for milk production rather than for riding and transportation, and this use could be rooted in practices associated with the early stage of dromedary husbandry in the southern Arabian Peninsula (

1,

7)."

Another study, same topic, 2015:

http://www.pnas.org/content/113/24/6588.full

"There are lots of additional interesting observations in the work of Almathen et al. (

3). For instance, their microsatellite data suggested the existence of demographic collapses before domestication, some ∼5,000–8,000 ya. They also revealed the presence of two major ancestry components within modern dromedaries. Both are represented throughout their entire distribution range, but the first is maximized in East Africa, whereas the second is most common to all other regions. This distribution suggests that the ecogeographic barriers from East Africa and/or the cultural differences (dromedaries there are predominantly used for their milk instead of riding and transportation) have limited the extent of the homogenizing process in this region. In addition, despite clearly belonging to a common population extending from North Africa to Southwest Asia, populations from isolated montane regions in the south of the Arabian Peninsula showed slight genetic distinctions. Here, the geographic accessibility of the regions thus seems to have also somewhat limited the extent of the homogenizing force. Surprisingly, the populations from South Arabia show minimal genetic distance to those populations from East Africa, and not North Arabia. It likely suggests an early introduction from South Arabia into East Africa by boats, through the Red Sea. When this took place is presently unknown, but could probably be inferred in the future using methods in statistical genomics exploiting genome-wide information (e.g., the over the 1 million SNPs identified while generating the two dromedary reference genomes) (

12,

13)."

I like the seaborne arrival theory, but think you are trying to push it too far back. So far, the very oldest camel bones in the Horn only go back to 1300 AD. There weren't any camels along the Red Sea coast in Hatshepsut's time.

30 years and I return to the same dusty Tuulo just as I left it.

30 years and I return to the same dusty Tuulo just as I left it.