The alchemist

VIP

New Methodology to control for study outcome heterogeneity and comparative risk assessment for increased quality and expert subject deliberation transparency

A study that tries to quantify the mean factor between risk exposure and disease. It claims that red meat is not as bad as previously posited by studies due to either weakness in constraints of the study methodology and various confounding elements or just unfounded (non-replicable) baseless outcomes altogether.

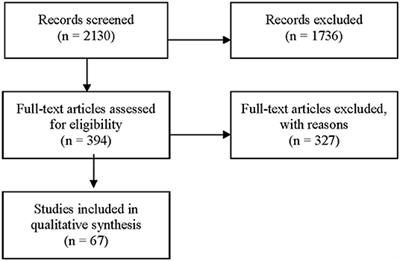

These researchers devised a new systemized way to assess the relationship between risk and outcome, tightening the bias gap from the uncertainty range shown in previous papers that had wide-ranging results (too many design problems).

“Our meta-analytic approach uses splines to estimate the shape of the risk function without imposing a functional form such as log-linearity, and can be widely applied to other risk–outcome pairs not included in this analysis. This flexibility is an important strength of our approach because many risk–outcome pairs do not have a log-linear relationship. When there are strong threshold effects, log-linear risk functions can exaggerate risk at higher exposure levels and obfuscate important detail at lower exposure levels. This more flexible approach helps identify the true shape of the risk function.”

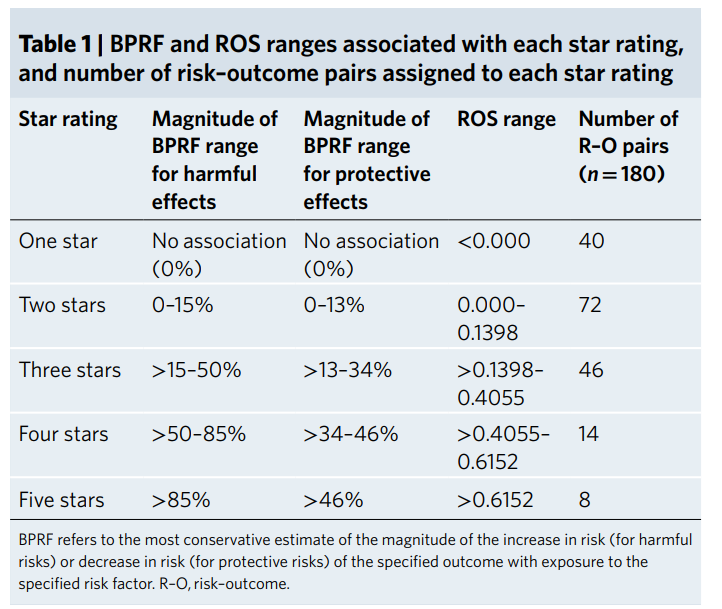

The star rating system is a comparative risk assessment tool:

Conservative estimates say there is a low risk (to stars) between ischemic heart disease and red meat consumption.

"Unprocessed red meat and ischemic heart disease (two stars). We identified 43 observations from 11 prospective cohort studies on unprocessed red meat and ischemic heart disease (Fig. 4)28. At an exposure of 50 grams per day, the mean relative risk is 1.09 (0.99–1.18) compared to 0 grams per day, and at 100 grams per day, it is 1.12 (0.99–1.25) (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table 4). In the analysis of bias covariates, we found that none had a significant effect. Trimming removed five observations that reported extreme values across the range of red meat consumption. There is no visual evidence or finding of potential publication or reporting bias (Fig. 4c). For unprocessed red meat and ischemic heart disease, the exposure-averaged BPRF is 0.01, essentially on the null threshold (Fig. 4a), equating to an ROS of 0.01, with a corresponding increase in risk of 1.04%. These findings led this risk–outcome pair to be classified as a (nominal) two stars, on the threshold between weak evidence and no evidence of association for the risk–outcome pair."

"For example, due to very high heterogeneity between studies, a conservative interpretation of the available evidence suggests that there is weak to no evidence of an association between red meat consumption and ischemic heart disease. There is, therefore, a critical need for more large-scale, high-quality studies on red meat consumption so policy-makers can make better-informed decisions about how to prioritize policies that address this potential risk."

A varied and healthy diet, with good amounts of veggies, is likely in the good range. Keep away from overconsumption of processed meat because that stuff is proven to cause diseases. That's my advice.

The study lists limitations, showcasing it is potentially a better system but not perfect.

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-022-01973-2

@Shimbiris @Sophisticate This is something you guys want to chew on.

A study that tries to quantify the mean factor between risk exposure and disease. It claims that red meat is not as bad as previously posited by studies due to either weakness in constraints of the study methodology and various confounding elements or just unfounded (non-replicable) baseless outcomes altogether.

These researchers devised a new systemized way to assess the relationship between risk and outcome, tightening the bias gap from the uncertainty range shown in previous papers that had wide-ranging results (too many design problems).

“Our meta-analytic approach uses splines to estimate the shape of the risk function without imposing a functional form such as log-linearity, and can be widely applied to other risk–outcome pairs not included in this analysis. This flexibility is an important strength of our approach because many risk–outcome pairs do not have a log-linear relationship. When there are strong threshold effects, log-linear risk functions can exaggerate risk at higher exposure levels and obfuscate important detail at lower exposure levels. This more flexible approach helps identify the true shape of the risk function.”

The star rating system is a comparative risk assessment tool:

Conservative estimates say there is a low risk (to stars) between ischemic heart disease and red meat consumption.

"Unprocessed red meat and ischemic heart disease (two stars). We identified 43 observations from 11 prospective cohort studies on unprocessed red meat and ischemic heart disease (Fig. 4)28. At an exposure of 50 grams per day, the mean relative risk is 1.09 (0.99–1.18) compared to 0 grams per day, and at 100 grams per day, it is 1.12 (0.99–1.25) (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table 4). In the analysis of bias covariates, we found that none had a significant effect. Trimming removed five observations that reported extreme values across the range of red meat consumption. There is no visual evidence or finding of potential publication or reporting bias (Fig. 4c). For unprocessed red meat and ischemic heart disease, the exposure-averaged BPRF is 0.01, essentially on the null threshold (Fig. 4a), equating to an ROS of 0.01, with a corresponding increase in risk of 1.04%. These findings led this risk–outcome pair to be classified as a (nominal) two stars, on the threshold between weak evidence and no evidence of association for the risk–outcome pair."

"For example, due to very high heterogeneity between studies, a conservative interpretation of the available evidence suggests that there is weak to no evidence of an association between red meat consumption and ischemic heart disease. There is, therefore, a critical need for more large-scale, high-quality studies on red meat consumption so policy-makers can make better-informed decisions about how to prioritize policies that address this potential risk."

A varied and healthy diet, with good amounts of veggies, is likely in the good range. Keep away from overconsumption of processed meat because that stuff is proven to cause diseases. That's my advice.

The study lists limitations, showcasing it is potentially a better system but not perfect.

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-022-01973-2

@Shimbiris @Sophisticate This is something you guys want to chew on.