[Grammar might be off due to Google translate, original source was Italian. Ignore the colonial undertones]

Italian Somalia is a climatically arid region, bathed by rains not sufficient for large-scale agricultural development, but it also has two copious rivers of water that descend from the Ethiopian plateau, the Uebi Scebeli and the Juba . It was therefore linked to the development of these rivers the study and then the agricultural exploitation in the period of our colonial presence. Of the two, the Juba is the most conspicuous as to the mass of water, but its valorization was hampered by the fact that until 1926 the right bank was part of the British colony of Chenia and our sovereignty began in that year following the agreements Italo-British aimed at applying the colonial territorial compensation provided in our favor following the common victory in the First World War. However, on this left bank, already under our sovereignty, the first Italian agricultural concessions were established, first of all that of Mr. Carpanetti already in 1905, but also that of Col. Frankestein (of Polish origin, but very Italian) and that of the company "Giuba d'Italia"and others. On the right bank there were some British dealers whose interests were safeguarded by the above-mentioned Italian-British agreements. Overall, the Juba dealers were a dozen and gathered in the Juba Agricultural Consortium, supported and valued by the Alessandra governmental farm .

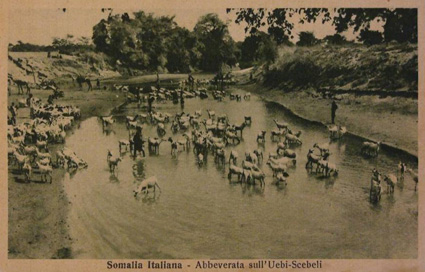

However, along the banks of the UEB Scebeli a far greater valorisation program developed. This river had the positive peculiarity of being very close to the cities of Mogadishu , which was the capital of the Colonia and Merca, which was the second city and, therefore, favored by the presence of outlet markets for products and landings able to favor the 'export. The pioneers of this civilizing enterprise were Romolo Onor (San Donà di Piave 1880 - Genale 1918) and Cesare Scasellati Scozzolini(Gubbio 1889 - Mogadishu 1929). The first realized in 1912 the experimental farm of the Government of Somalia which in the following years became the fulcrum of the great Genale agricultural consortium. The second was the main engineer who carried out the great colonization project designed by that great Italian, great explorer and great pioneer who was Luigi di Savoia Duca degli Abruzzi . Both these gigantic achievements deserve a monograph that illustrates the design details, construction and agricultural characteristics, but here I just want to give an account so that, at least in a general way, you can fix in memory that great effort that honors those who made it and l 'Italy.

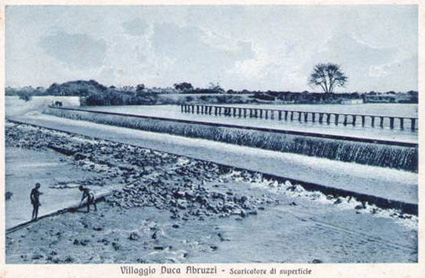

If the river Uebi Scebeli ( river of leopards, the name in the Somali language) had the advantage of being close to the coastal cities, but presented a not inconsiderable disadvantage due to the intermittence of its flow that alternates a double full season (February-March and July-September) to a just as double lean season during which the river comes to interrupt the continuity of its course. Agricultural exploitation, linked to the use of river water, was thus dependent on the storage of water during the flood period. With the end of the world war and the political and economic stabilization of Italy, the program of valorization of our colonies and, in this case, the colony of Italian Somalia also began. The importance and the cost of the necessary hydraulic works was such as to transcend the financial possibilities of individual dealers. There was a need for substantial capital and a firm determination to make long-term investments. On impulse of theDuca degli Abruzzi , the SAIS "Italo-Somali Agricultural Company" was established in 1920, which reached the paid-up capital of 35 million Lire in 1924 and obtained a large concession of 25,000 hectares. In the same years the Agricultural Genal Consortium was organizedand hydraulic river barrier works were carried out. Two large dams provided for the storage of the flood waters and to divert them through hundreds of kilometers of irrigation canals to the smallest units organized in the region. Thus, in a few years, two vast arid territories were transformed into two large, green productive economic realities, crossed by hundreds of kilometers of roads, narrow-gauge railways, telegraph and telephone lines. For the Somali farmhouse population, dozens of villages were built, while the production and processing centers of the products were made from scratch and were baptized by Villaggio Duca degli Abruzzi (usually abbreviated Villabruzzi ) that of the SAIS andVittorio d'Africa , that of the Genale Consortium. In these two centers the population of Italian technicians and administrators was concentrated, as well as the processing plants: cotton ginning and pressing plants, oil mills for pressing the various oil seeds produced (cotton, peanuts, castor, sesame, etc.), saponifici, mechanical factories for the assistance and repair of agricultural machinery, power plants)

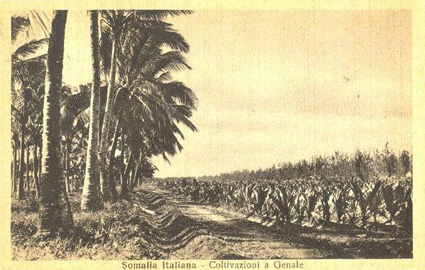

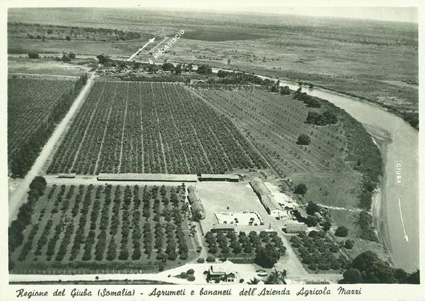

The productions initially concerned mainly cotton, while the other productions were considered subsidiaries. The cotton Sakellaridis, ie the Egyptian variety, perhaps the most valuable in the world, was a product for which the Italian industry was totally dependent on foreign countries and, therefore, aimed to reduce this dependence, without considering that it had a price in the 20s highly remunerative. With the great crisis, however, the price of cotton, like those of many other raw materials, depreciated to the point of losing, at the beginning of the 30s, 50% of its value. Thus a productive conversion was imposed that could save the economic efficiency of the colonizing enterprises, awaiting the resumption of quotations. This challenge was also dealt with and resolved brilliantly. The SAIS, for its part, intensified the production of sugar cane for the transformation of which had built a large sugar factory, the first of East Africa, focusing on this product that had growing consumption within the newly formed AOI and also in Italy; while the Genale Consortium focused on the cultivation of the banana, whose consumption was in very strong rise in Italy and that until 1929 represented a marginal cultivation. The Italian government granted this product maximum protection by reserving the Somali production the monopoly of the importation in Italy. The RAMB Regia Azienda Monopolio Banane was established with the task of importing and distributing the product in the internal market. A large factory for packing and exporting was built in Vittorio d'Africa, while for the transport of the product the construction of 7 banana ships equipped with refrigeration systems was carried out and which shuttled between Merca, which became the "port of the bananas " and the Italian maritime cities.

With the end of the great world economic depression, in the years 1938-1939, even cotton and other agricultural products returned to more lucrative prices and everything had foreseen a future of expansion and success for the agricultural colonization in Italian Somalia, when the war unfortunately, he interrupted this great project forever, of which today, due to human folly, only the ruins remain and there is the risk of losing its memory.

Last edited: