General Asad

And What Is Not There Is Always More Than There.

Somalis in Minnesota and the world are watching the case of an East Grand Forks mother whose children were removed by child protective services. Somali community members believe she’s being treated unfairly, but the facts are not black and white.

CROOKSTON, Minn. — More than 100 Somali people packed the hallways of the Polk County Courthouse Monday, praying and then pressing officials to explain why the six children of a Somali mother had been taken away from her.

Nimo Khalif, 33, a widow who came to America from a refugee camp in Kenya in late 2014, had been raising the children ages 10 months to 16 years alone in East Grand Forks. Suddenly, the kids were in the custody of Polk County child protective services.

A distraught Nimo posted a video pleading in Somali for help. She said she wasn’t told why the children, ages 10 months to 16 years old, were removed and didn’t know what to do. Later, she would describe it as a “kidnapping.”

The Somali community across Minnesota responded. The widely shared video helped deliver supporters to the courthouse Monday, including many who drove nearly five hours from the Twin Cities.

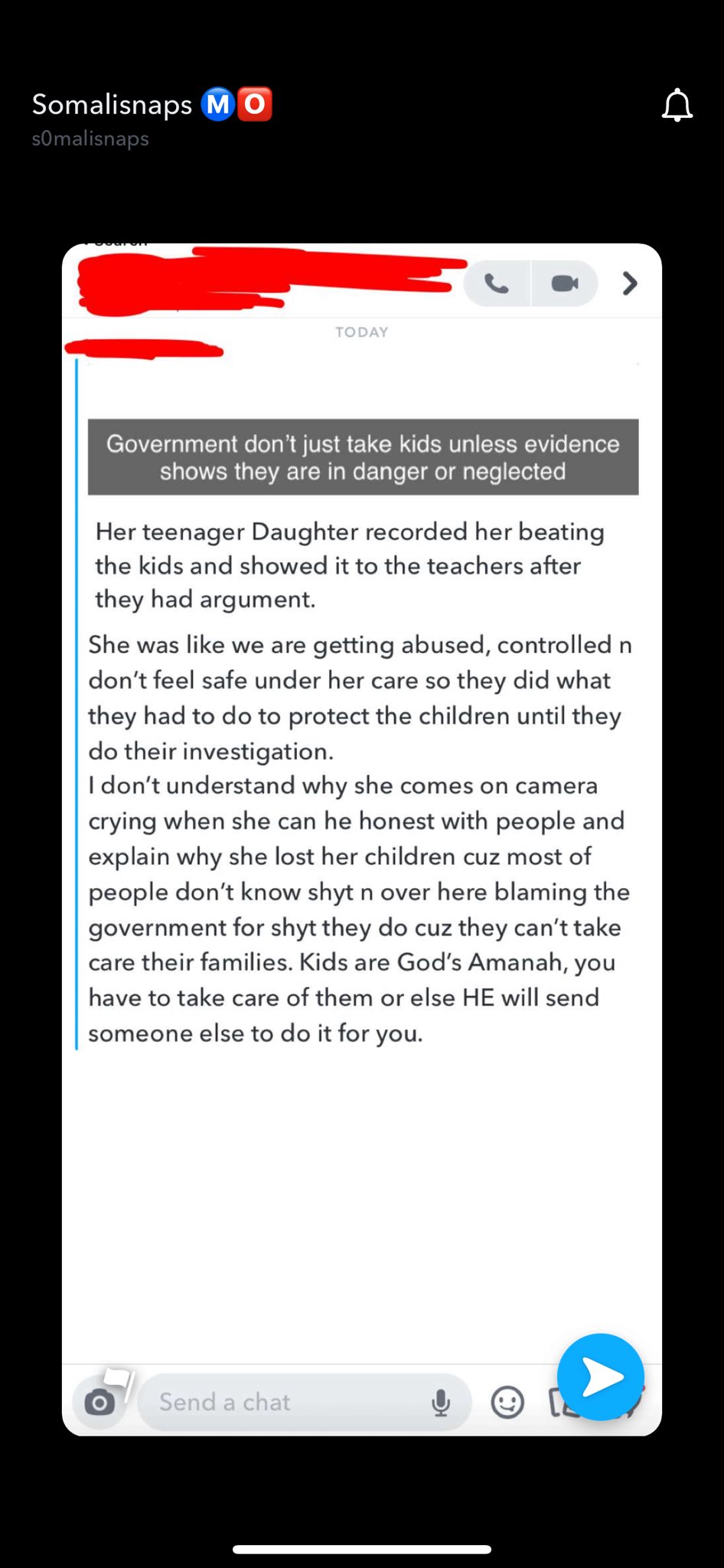

They left without answers. It turns out the case is more complicated than those responding to Nimo’s pleas might have realized. While concerns remain in the Somali community that Nimo’s being treated differently because she’s Somali, the facts are not yet black and white.

‘Possible child abuse’

It began when one of Nimo’s daughters allegedly told a teacher in an email that she did not feel safe at home and was afraid to live with her mother.

Schools are required to report any suspected cases of abuse, so the East Grand Forks police were brought in. A school resource officer from the department began investigating in mid-January, and then got the county’s social services department involved.

“We had reports of possible child abuse and neglect,” police chief Michael Hedlund told Sahan Journal. After interviewing the children, “a joint decision between social services and our officers were that it was in the best interest of the children that they be removed at that time.”

On Jan. 22, social services workers and the police came to the schools of Nimo’s school-age children, ages 16 to 6, and took them into protective custody.

Nimo said she did not know where the children were or what had happened. She said she left the 10-month-old baby boy she was breastfeeding with a friend as she searched for the other children.

She said she was summoned to the police department, where she learned what had happened to her school-age children. Nimo said she reluctantly told them where the baby was after being threatened with arrest.

Hedlund said the case is still a police matter, although Nimo has not been arrested or charged with a crime. The chief said authorities would wait for the social services department to complete its investigation before they determine their next step.

“Anytime our social services gets involved, the concern is there’s some issue in that family,” he said. “It could be just a parent-child disagreement.”

That belief — that what’s happening in Polk County may turn out to be a misunderstanding or simple family disagreement — has frustrated her supporters and bred mistrust of the process.

Local authorities appear to be doing their work by the book, but it’s unlikely they’ve been in a situation where a new immigrant community has collectively pushed for more information on a child custody case.

Despite intense interest from the Somali community, Karen Warmack, director of Polk County Social Services, declined to give details about the case.

“I am not able to share any particulars about the case because of any confidentiality or confirm or deny what’s happening,” Warmack said.

CROOKSTON, Minn. — More than 100 Somali people packed the hallways of the Polk County Courthouse Monday, praying and then pressing officials to explain why the six children of a Somali mother had been taken away from her.

Nimo Khalif, 33, a widow who came to America from a refugee camp in Kenya in late 2014, had been raising the children ages 10 months to 16 years alone in East Grand Forks. Suddenly, the kids were in the custody of Polk County child protective services.

A distraught Nimo posted a video pleading in Somali for help. She said she wasn’t told why the children, ages 10 months to 16 years old, were removed and didn’t know what to do. Later, she would describe it as a “kidnapping.”

The Somali community across Minnesota responded. The widely shared video helped deliver supporters to the courthouse Monday, including many who drove nearly five hours from the Twin Cities.

They left without answers. It turns out the case is more complicated than those responding to Nimo’s pleas might have realized. While concerns remain in the Somali community that Nimo’s being treated differently because she’s Somali, the facts are not yet black and white.

‘Possible child abuse’

It began when one of Nimo’s daughters allegedly told a teacher in an email that she did not feel safe at home and was afraid to live with her mother.

Schools are required to report any suspected cases of abuse, so the East Grand Forks police were brought in. A school resource officer from the department began investigating in mid-January, and then got the county’s social services department involved.

“We had reports of possible child abuse and neglect,” police chief Michael Hedlund told Sahan Journal. After interviewing the children, “a joint decision between social services and our officers were that it was in the best interest of the children that they be removed at that time.”

On Jan. 22, social services workers and the police came to the schools of Nimo’s school-age children, ages 16 to 6, and took them into protective custody.

Nimo said she did not know where the children were or what had happened. She said she left the 10-month-old baby boy she was breastfeeding with a friend as she searched for the other children.

She said she was summoned to the police department, where she learned what had happened to her school-age children. Nimo said she reluctantly told them where the baby was after being threatened with arrest.

Hedlund said the case is still a police matter, although Nimo has not been arrested or charged with a crime. The chief said authorities would wait for the social services department to complete its investigation before they determine their next step.

“Anytime our social services gets involved, the concern is there’s some issue in that family,” he said. “It could be just a parent-child disagreement.”

That belief — that what’s happening in Polk County may turn out to be a misunderstanding or simple family disagreement — has frustrated her supporters and bred mistrust of the process.

Local authorities appear to be doing their work by the book, but it’s unlikely they’ve been in a situation where a new immigrant community has collectively pushed for more information on a child custody case.

Despite intense interest from the Somali community, Karen Warmack, director of Polk County Social Services, declined to give details about the case.

“I am not able to share any particulars about the case because of any confidentiality or confirm or deny what’s happening,” Warmack said.

You don't have permission to view the spoiler content.

Log in or register now.