Since I moved to Maine six years ago, I’ve heard a fair number of people tell the story that Somali immigrants have turned Lewiston into the most crime-ridden city in Maine. Two years ago, I decided to stop listening to stories and start looking at actual crime statistics. The truth is that the city of Lewiston is far from the most crime-ridden city in Maine; it ranks right in the middle of other cities in Maine, with about half above and half below. Looking further into misconceptions about Somalis in Lewiston, I shared federal crime statistics indicating that actually, the period before Somali immigrants began settling in Lewiston is characterized by a much higher crime rate (in both property crime and violent crime) than the period after Somali immigrants started settling in Lewiston. The drop in crime rates in Lewiston has occurred while more Somali immigrants have moved to Lewiston, and while other Maine cities without Somali immigrants have seen their crime rates go far, far up.

But there’s just no convincing some people. About a week ago, a visitor named Matthew shared this comment:

“I acknowledge and appreciate that these Somali’s probably had very difficult lives back in their homeland. But as a citizen of the United States and a resident of Maine, I find myself asking what benefit are we getting from allowing these folks immigrate here? How are they making our country and state a better place? I’m all for immigration, and bringing the best and brightest minds to the US so our nation can prosper. But these people aren’t the best and the brightest, they aren’t the next Steve Jobs, they are destitute folks who come here and immediately get caught in a cycle of generational Welfare. They criticize our cultural values, they accuse the majority population of racism, and they preach a religion that in certain respects is brutal and medieval. They bring down the average IQ of our population (not a pretty fact, but true), and they burden our schools and business with increased language requirements and cultural sensitivity training.”

I asked, in return,

“Matthew,

“Do you have documentation that Somali immigrants in Lewiston:

* are not the best?

* are not the brightest?

* do not have among them the next Steve Jobs?

* are, having come to Lewiston beginning in 2000, caught in a cycle of intergenerational welfare?

* criticize American values?

* accuse the majority of racism?

* have a lower than average IQ than others?

“I agree with you when you say “let’s look at the bottom line.” The bottom line is that you’ve made these specific claims about Somali immigrants to Lewiston. Do you have specific documentation to support these specific claims? If not, please retract them.”

Matthew’s response after that point centered on the claim that Somalis are a low IQ variety of human being:

“Thousands of IQ studies have been conducted worldwide, and as anyone who follows the psychometric literature knows, Africa and many other third world regions score very poorly. Somalia’s average scores are in the 59-71 range, which means that the average individual from that nation is in the mildly retarded classification. (1)

(1) http://memolition.com/2014/02/27/who-are-the-smartest-people-on-earth-world-map-of-average-iq-scores/“

Let’s look at that link. Go ahead. Click it. You’ll see a highly infographicky map with nice production values. But the website isn’t the source of these “thousands of IQ studies” about “Somalia’s average scores in the 59-71 range.” No, the website refers to a book of “research” by Richard Lynn and Tatu Vanhanen. You can read statistical extracts from their book, IQ and the Wealth of Nations, right here. I found a full copy of the book myself. I read it.

You may find it hard to believe what I found — but then again, perhaps you won’t be so surprised after all.

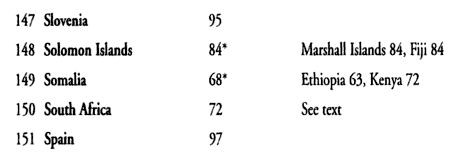

Here’s the snippet in the table in which “Somali IQ” is supposedly reported:

There it is — according to the authors of that book, Somalia has an IQ of 68. It’s an odd assertion to begin with, because after all nations don’t have IQs. Individual people do. This is a classic ecological fallacy. But it’s worse than that. You may find yourself asking what that little asterisk next to the 68 is for. Is it a multiplication symbol? No. The asterisk leads to a notice on another page that in the case of an asterisk, they didn’t actually collect any results of any IQ tests at all. Not a single person from Somalia had their IQ score measured for the book, or for any study used by the authors of the book. There are literally zeropoints of data to support an “IQ Score” of 68 for Somalia.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

A New Low in Race-Based Immigrant Bashing: “Proving” Somalis Have Low IQ Without Measuring Somali IQ

- Thread starter land owner

- Start date

https://web.archive.org/web/2017051...s-have-lower-iqs-without-measuring-somali-iq/So where does the oddly precise “68” come from? Look to the right. Do you see the text “Ethiopia 63, Kenya 72”? If you read the “methodology” section of the book, you’ll find out that when the authors had no observations at all for a country, that didn’t stop them. They just declared the IQ of that country to be the average IQ of the studies of the often very few people subjected to psychometric tests in adjacent countries. Somalia is next to Yemen, Djibouti, Ethiopia and Kenya. Djibouti and Yemen aren’t counted, because the authors don’t have access to any data for those nations. So they:

The authors literally just looked at Ethiopia’s “score” and Kenya’s “score” and picked a number in the middle and proclaimed that Somalia has an IQ score of 68. That’s their “methodology.”

- took average IQ scores from the studies they dredged up in Ethiopia and Kenya,

- then assumed that the scores in Ethiopia and Kenya were representative,

- then assumed that “Somalia’s IQ score” was an average of Ethiopia and Kenya’s, but not Djibouti’s and Yemen’s, “IQ scores”

- all the while mistakenly forgetting countries don’t take IQ tests.

It gets worse. What are Ethiopia’s “score” and Kenya’s “score” based on? As is typical for the studies used in the authors’ book, small numbers of scores derived from tests of odd and unrepresentative sets of people.

Let’s start with “Ethiopia’s IQ.” If you look up the notes for yourself and follow the citations, you’ll find out that the Lynn and Vanhanen didn’t find any measurements of anyone’s IQ in Ethiopia, either. The best they managed was to gather 250 IQ scores from 14-to-15-year-old Ethiopian Jewish immigrants to Israel, living in Israel. The source was a 1991 study by Shlomo Kaniel and Shraga Fisherman’s, “Level of performance and distribution of errors in the Progressive Matrices test: A comparison of Ethiopian immigrant and native Israeli adolescents” in the International Journal of Psychology. These youths had been moved to Israel only one year before and in their lives in Ethiopia had been especially deprived, even compared to their fellow countrymen and women:

“In Ethiopia, Jews generally lived in small villages of 50-60 families, remote from urban centers…. Participation in formal elementary school was impeded by the long distances between home and school, travelled on foot. High school education necessitated either a move to the city, at great expense, or prohibitively difficult travel. Consequently, few Ethiopian Jews were able to receive formal education…. Prior to their exodus, most had never seen electricity, a telephone, or any technological instruments. In Israel, they must adjust to climatic differences, life in urban centers, a new language…” (p. 26)

But Lynn and Vanhanen take this astoundingly unusual small group of young, uprooted, uneducated youths not even living in Ethiopia, discover that their “IQ scores” are unsurprisingly low, and adopt that average score as the “Ethiopia’s IQ.”

What about the estimate for “Kenya’s IQ?” In a 2010 paper published in the journal Learning and Individual Differences, Jelte M. Wicherts , Conor V. Dolan, Jerry S. Carlson and Han L.J. van der Maa revealed that Lynn had excluded a sample from his estimate for Kenya because the IQ in the sample was too high.

Biasing the scores from one country, importing scores for another country from a wildly unrepresentative group, and using both to charm up a completely fictitious average score for a third nation, Somalia. That’s the basis for Matthew’s decision to reject Somali immigrants to Lewiston. It’s wrong factually. And because it’s wrong factually, it’s wrong morally.

As I said, there’s just no convincing some people. When I pointed out that there were actually no observations of IQ in Somalia to back up Matthew’s claim, did Matthew change his mind. No. Instead, he simply refused to confront that fact.

Frankly, my hope in writing this isn’t for Matthew. My hope is that someone else reading this, someone whose mind isn’t quite so committed to a falsehood, will be willing to let that falsehood go.

action is the real measure of Intelligence not some stuiped test or books.

This iq theory is ridiculous. If it's real then how come Nigerians are doing better than the chinese rich kids in the UK unis? why do they get angry when they come second to a hard workign african or brown immigrant? most cadaan here underperform in the uk anyway. IQ is a statistic made up by the white colonisers to justify slavery and their fantasies of being the superior race.

They claim they have the highest iq and cry over jews and immigrants conspiring together to replace them. Do they not understand the meaning of high iq? then how can they have high iq if they see themselves losing the world and their minds. This is why they go around shooting innocent ppl because in the age of widespread knowledge and wisdom, they can't compete with other races and are experiencing a melt down.

They claim they have the highest iq and cry over jews and immigrants conspiring together to replace them. Do they not understand the meaning of high iq? then how can they have high iq if they see themselves losing the world and their minds. This is why they go around shooting innocent ppl because in the age of widespread knowledge and wisdom, they can't compete with other races and are experiencing a melt down.

AhmedSmelly

I am an offical nacas. too honest

Well Somalispot users are no better than the White supremacist. They are different but the same. I started believing that Somali people had 68 IQ because of you guys. I still believe they have 68 IQ. You guys have transformed me to a Qabil supremacist.

Wow a white person vindicates us. All's well with the world...

action is the real measure of Intelligence not some stuiped test or books.

This iq theory is ridiculous. If it's real then how come Nigerians are doing better than the chinese rich kids in the UK unis? why do they get angry when they come second to a hard workign african or brown immigrant? most cadaan here underperform in the uk anyway. IQ is a statistic made up by the white colonisers to justify slavery and their fantasies of being the superior race.

They claim they have the highest iq and cry over jews and immigrants conspiring together to replace them. Do they not understand the meaning of high iq? then how can they have high iq if they see themselves losing the world and their minds. This is why they go around shooting innocent ppl because in the age of widespread knowledge and wisdom, they can't compete with other races and are experiencing a melt down.

TL;DR: White supremacists conducted flawed IQ tests on Falasha Ethiopian children (63) and Kenyans (72) but not on Somalis so they gave us their average which was 68.

I already read this article but it bears repeating.

Make sure y’all embarrass any alt right spewing that 68 garbage with this infoWell Somalispot users are no better than the White supremacist. They are different but the same. I started believing that Somali people had 68 IQ because of you guys. I still believe they have 68 IQ. You guys have transformed me to a Qabil supremacist.

Richard Lynn has been exposed for manipulating and falsifying data to fit his racist agenda check this out

https://racialreality.blogspot.com/2011/08/devastating-criticism-of-richard-lynn.html?m=1

https://racialreality.blogspot.ae/2011/11/african-iq-and-the-flynn-effect.html

https://racialreality.blogspot.ae/2013/11/calling-out-jayman.html

https://racialreality.blogspot.com/2011/08/devastating-criticism-of-richard-lynn.html?m=1

https://racialreality.blogspot.ae/2011/11/african-iq-and-the-flynn-effect.html

https://racialreality.blogspot.ae/2013/11/calling-out-jayman.html